"Low-Res Consciousness: Alien Minds and Sparse Experience" by Helen Yetter-Chappell

Helen Yetter-Chappell is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Miami. Her work explores the nature and structure of possible worlds and possible minds, and the ways in which the two might illuminate each other. Her recent book, The View From Everywhere, developed a novel nontheistic form of idealism – with important implications for the nature of perception and the relationship between our minds and our bodies. It provided a uniquely optimistic account of our place within, and our ability to comprehend, reality. She is currently working on a new book arguing that both experience and reality itself can be radically sparse – “leaving open” things that might have intuitively seemed impossible.

The following essay by Helen was an honorable mention in the 2025 Berggruen Prize Essay Competition.

Essay

"Low-Res Consciousness: Alien Minds and Sparse Experience" by Helen Yetter-Chappell

Download the pdfHow might an alien mind perceive the world? How might an AI? These may seem to be questions we simply cannot answer. But I’ll argue that when it comes to the structure of experience, there’s enormous opportunity to expand our view of what’s possible. I’ll show that experiences can be radically more “sparse” or schematic than we might initially suppose: There can be experiences as of objects that have color, but no particular color; experiences as of triangles that are neither equilateral, isosceles, nor scalene (for the relationships between the lengths of sides and angles are left open). Such experiences have long been taken to be impossible. But while they may be impossible for us, they are possible for the right sort of mind. I’ll introduce a framework for thinking about alien experiencers and alien experiences, drawing on comparative neurobiology, and will use this to argue for the possibility of radical experiential sparseness – a possibility that is particularly relevant to digital minds, who have immense potential for sparse experience.

Humans have long been fascinated by the idea of alien life. As early as Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle’s 1686 dialogue Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, writers have imagined what life on other planets might be like, how it might differ from life as we know it, and how it might be shaped in novel ways by alien . By the 19th century, there was widespread interest in alien lifeforms, which has continued into present day science fiction and scientific aspirations to discover life on other planets. Why this fascination with alien life? Undoubtedly part of it arises from wondering whether Earth is unique in hosting life. But a part of it stems from curiosity about the possible beings themselves. What might they be like? If they’re conscious, how might they think? Feel? Perceive their worlds? How much variation is there in what sorts of conscious beings are possible? Much as we might wonder about the range of possible worlds, so too, it’s fascinating to wonder about the range of possible experiencers.

Alien consciousness is no longer something that we have to fantasize about finding. With the rise of Artificial Intelligence, it’s plausible that we may soon create alien . Much has been written about the generic possibility of conscious AI. But very little attention has been given to what sorts of experiences such entities might have. What might it be like to be an AI? Just how wildly different might AI experiences be?

These may seem to be questions we simply cannot speak to. As much as we might know about the physiology of a bat, this can never reveal to us what it is like to be a . Likewise, no matter how much we might learn about the physiology of an alien life form – or the architecture of an AI – we will never be able to know what their experiences feel like. Insight into the qualitative nature of alien experiences is clearly impossible: such insight can only be had by experiencing the alien’s perspective “from the inside” – rendering it no longer alien. It’s difficult to see how we could even speculate about alien experiences, beyond postulating their existence.

But while we cannot hope to grasp the qualitative nature of alien experiences, this does not mean that we must remain wholly in the dark concerning experiences different from our own. Part of what makes our experiences feel the way they feel is their structural features. And when it comes to the structure of experience, there’s enormous opportunity to expand our view of what’s possible.

I’ll argue that experiences can be radically more “sparse” or schematic than one might initially suppose. There can be experiences as of objects that have color, but no particular color; there can be experiences as of objects standing in spatial relations to one another, but not any particular spatial relations; there can be experiences as of triangles that are neither equilateral, isosceles, nor scalene, for the relationships between the lengths of sides and angles are left open. Such experiences have been taken to be impossible since at least the 1700s. Enlightenment philosopher George Berkeley made the manifest incoherence of such experiences the cornerstone of one of his most famous arguments – the argument against Lockean abstract general ideas. As Berkeley wrote,

If any man has the faculty of framing in his mind such an idea of a triangle [that is neither equilateral, isosceles, nor scalene], it is in vain to pretend to dispute him out of it, nor would I go about it. All I desire is that the reader would fully and certainly inform himself whether he has such an idea or no. And this, methinks, can be no hard task for anyone to .

I’ll argue that such experiences are possible – perhaps not for us, but for some possible creatures. While we cannot have experiences as wild as a triangle with no particular dimensions, I’ll argue that our experiences can exhibit a degree of sparseness. I’ll introduce a framework for thinking about alien experiencers and alien experiences, drawing on comparative neurobiology, and will use this to argue for the possibility of radical sparseness – for the right sort of being.

Sparse Experiences

What would it be for an experience to be sparse? The rough idea is that sensory experiences can “leave open” certain details that cannot be left open in reality, and that we might have thought could not possibly be left open in experience. Other philosophers have described the phenomenon in different terms. Rick Grush describes it as “generic

Roughly the idea is that, for example, when reading a page of text, a word on the page in the visual periphery is phenomenally present, but not as the specific word it is, just as the generic text word.

James Stazicker and Michael Tye describe it as the idea that consciousness experiences can be I don’t think that such experiences involve indeterminacy – a lack of settledness – but rather that they involve a determinate absence or “leaving out” of a sort that one might have thought impossible: leaving the specific hue out of the red; leaving the location along the y-axis out of the bird’s location; leaving the relations between the angles out of the triangle.

My claim is not the simple claim that mental representations can be sparse. That’s easy! Just think: “A man walks into a bar...” Viola! You’ve formed a sparse mental representation. Is the man tall or short? Wearing a blue overcoat or naked? None of this is specified by your thought. The interesting claim – the claim we’re going to explore here – is the claim that sensory experiences (things like perceptual experiences and mental imagery) can be sparse. The very way these experiences feel can leave things out.

Could there be a sensory experience (say, an imagining) of a man walking into a bar, where nothing else is specified? The idea seems wild – perhaps manifestly impossible. Just try to imagine this. It seems inevitable that you imagine the man as wearing something or other (or that you imagine him as wearing nothing). Your imagining can’t simply leave this unspecified! It’s natural to think that sensory experiences (imaginings and perceivings) are, in this respect, picture-like: While a sentence can say that a man walks into a bar (and not say anything more), a picture of a man walking into a bar cannot help but say something more.

But reflecting further on pictures, perhaps the claim that experiences can be sparse is not as wild as it sounds. Maps are pictures that specify a great deal about the world. But they can also leave a great deal unspecified. A map might represent a mountain range (as a cluster of triangles) without representing the number of mountains or their heights. It might represent a river (as a blue line) without saying anything about its width or its depth. A map’s legend dictates that lines in a triangle pattern represent mountains, and blue lines rivers. Likewise, I might imagine the landscape of Colorado in a map-like way, with triangles in my mental image representing the Rockies. There’s a sense in which this imagining is underspecified, insofar as what the experience is taken to represent is not fully fleshed out. Likewise, a stick figure of a man inside of a square that says ‘bar’ might be taken to represent a man walking into a bar, without saying anything as to his height or his attire.

Unfortunately, none of these simple examples is a case of sparse experience in my sense. While it’s left open what we take the map (or the map-like imagining) to represent or ‘say’ about the world, in each case, the form of the image (of the imagining) is fully fleshed out. There’s a precise fact of the matter about each line of the map, and each experiential bit of the map-like imagining. What’s left open is merely what we interpret them to represent. Likewise, while a stick figure could represent any man, there’s still a precise answer as to the height of the figure relative to the ‘bar’, the color of his outline, etc.

This sort of sparseness – what we might call representational (or interpretational) sparseness – is undeniable. But it’s also uninteresting. I’m going to argue for something far more radical: that the very form of the experiences can be “left open”. There can be an experience that not only represents redness generically, but that does so by being a red without being any specific type of red. There can be an experience that not only represents triangles generically, but that does so by being a triangle without being any specific type of triangle. (If this sounds wild, you’ve understood it right!) Let’s call this sensory sparseness.

Before we get to examples of sensory sparseness, let’s pause to consider an example of an experience that one might mistakenly believe to involve sensory sparseness (but is really just representational). Michael Tye suggests blur as an example of indeterminate visual

You are at the optometrist, staring at a chart of letters. You see the fifth row, just as you do the top five rows, but you see it through a blur. This blur prevents you from identifying the letters. There is indeterminacy in your visual experience. As you stare at the letters in the fifth row (and also the sixth), you cannot tell where their component letter segments are situated exactly and so you cannot identify the letters

Here, your experience is indeterminate with respect to the exact positions of the letter segments in the fifth row down and relatedly with respect to the identities of the letters.

In the case of blur, we do not take our experience to represent a world that is precisely the way the picture looks, or any other precise way. What we interpret our experience as ‘saying’ about the world leaves the details open. But, though there is representational sparseness, there is not sensory sparseness: Every detail of the experience is fully fleshed out. We can see this by the fact that a printer could capture the precise form of the experience.

There is nothing “left open” about this experience any more than there is something “left open” by the printer. Every pixel of the paper is specified, as is every ‘pixel’ of your experience. What is left open is simply what we interpret the experience as telling us about the world.

A Case Study: Peripheral Color Vision

Before we get to really wild cases of sensory sparseness, let’s explore an example that’s closer to home. While blurred vision is not an instance of sensory sparseness, we do routinely have sparse experiences. Peripheral color vision is a prime example.

As I look out at my backyard, it’s tempting to think that the experience includes maximally specific colors all throughout. I check the Magnolia tree – yes, it’s a precise shade of green. I look at the deck – yep, a precise shade of brown. The sky? A precise shade of blue. But this is an illusion. As we shift our attention to scan our visual field, our eyes invariably skitter through space, shifting the region of our retina upon which inputs are centered. Even if visual experiences in the central (foveal) visual field are maximally specific, there is good reason to think that colors in the periphery are examples of sensory sparsity.

I focus my eyes on a point ahead of me and attend to the (lavender) water bottle sitting in my peripheral field. When I do, the water bottle seems colored. But there is no specific color that it seems to be. It’s clearly light. It’s clearly not red. But that’s all I seem to be able to say.

It’s not just that I know that the water bottle is colored. It positively looks colored. In this, it feels quite different from the experience of seeing the water bottle in dim light. In sufficiently dim light, my raw visual experience is entirely shades of grey. I know that the water bottle is colored. But the pure visuals don’t seem this way. The experience of the water bottle in dim light seems fully spelled out (in greys), even if we judge this not to be the reality of the scene.

By contrast, the water bottle seen in my peripheral field doesn’t seem grey. And it doesn’t seem lavender. And it doesn’t seem blue. There isn’t any specific shade that it does seem to be... And yet it seems to be colored.

Let’s grant this. The experience seems to be sparse. Does that mean that it is sparse? Seemings don’t always translate into realities. A dark figure seen at night might seem like a cat, when it’s really a racoon.

There’s a live debate among philosophers as to whether the seeming of an experience can come apart from its But we can make the case for the possibility of sparse experiences without wading into this debate – by using the conjunction of our apparent experiences and the underlying neurophysiology of the experience to make an inference to the best explanation.

Let’s start with the physiology of color vision. Our retinas have two types of light-sensitive cells: rods (which simply detect the presence of light, and enable vision in low light environments, but provide no color information), and cones (which respond differently depending on the wavelength of light). Information from the retina is passed on to the visual cortex, where further levels of processing occur. The interesting thing for our purposes is the difference between the intake and processing of information in the central (foveal) field of the retina, compared with the periphery. In the centermost region of the retina, there are orders of magnitude more cones per mmÇ than in the This means that we’re taking in far less information about the colors of objects in the periphery than we do for objects in our foveal field. Moreover, this difference is magnified by the processing of the visual cortex, where a single degree of visual angle in the foveal field takes up far more cortical surface area in the visual cortex than a degree in the peripheral Less information is taken in initially about the colors of objects in the periphery. And at every step of our processing of the inputs, more information is pooled and averaged, with fewer of the details preserved. And we’ve seen that as a result of this, it feels to us like colors in the periphery are sparse: objects seem to be colored, without seeming to be any precise color. Putting this together, we have a compelling basis for thinking that peripheral color experiences not just seem, but really are sparse.

When Introspection and Neurophysiology Converge

Humans have a “blind spot” – a place in the eye where the optic nerve attaches to the retina, and there are no light-sensing cells. With both eyes open, inputs from the opposite eye can supply the missing information. But, curiously, even when we close one eye, so that we are literally taking in no information about the region of space corresponding to the blindspot, there doesn’t seem to be a gap in what we experience. Our brains “hallucinate” content into the gap. An alien looking at the physiology of the eye might expect that when we close one eye, we’d have an experience with a hole in it. But we know that one can’t read off our experience from our physiology in this way. We know that we don’t experience such a hole: the experience is continuous, even if the inputs are not.

But now imagine that we’re exploring other planets and discover a kind of one-eyed alien. They’re conscious and eventually we become able to communicate with these aliens. It turns out they have a similar physiology to their eyes – with an optic nerve attaching to a retina. But – unlike humans with one eye closed – these aliens report seeming to experience a gap in their experience, which corresponds perfectly to the point where their optic nerves attach to their retinae.

One hypothesis would be that the aliens’ experience is, in fact, holey. Simple and elegant. An alternative hypothesis would be that – although the perceptual inputs are sparse and the experience seems to have a hole – actually, the aliens’ brains hallucinate a filling in of the gap (much as brains fill in our blind spot) ... but that for some reason this filled-in experience is inaccessible to the aliens.

While it’s possible for there to be beings that work this way, it involves hypothesizing some pretty bizarre contortions. When the apparent experience matches the physiology, our default assumption should be that the appearance is the reality. Given that our brains take in sparse information about peripheral color and process this in ways that continue to degrade the informational richness, the most plausible explanation for the fact that the resulting experiences seem to be sparse is that they really are sparse.

We have our first example of a sparse experience.

Sparseness and Space

How far can sparseness extend? Could spatial relations be “left out” in the same way?

As I look out my office window, the spatial relations between building, trees, windows, and students all seem perfectly precise. As I imagine animals in a forest, it’s natural to think that there must be a fixed answer to the spatial relationship between the squirrel and the bird. The color of the bird may be left open, but surely it’s fixed that the bird is (say) to the left of and above the squirrel. How could one experience a bird as located somewhere without it seeming to be here or there or there?

Surprisingly, we can make a straightforward empirical case for this possibility, analogous to the argument for sparse color experiences. While our visual experiences may typically present objects as having precise spatial relations, this can break down – particularly during rapid movement. We are typically quite good at judging the sizes of angles. You have no difficulty discriminating a 60 degree angle from a 90 degree one. And yet, when shown an angle rotating at 2.5x per second, we’re only able to determine with 75% accuracy between the actual angle and angles 40 degrees This is standard for rapidly moving visual

As in the case of peripheral color experiences, it is not simply that our performance or our experiential reports suggest that our experience fails to present us with precise angles. The neurophysiology backs up our self-reports.

Even in situations without rapid movement, it’s difficult to deny a degree of sparseness in our spatial experiences. Perhaps my experience of the books scattered about my desk reveals their relations down to the nearest millimeter – but it seems extremely implausible to think that my experience presents this book as seeming to stand a precise number of nanometers away from that one. This may seem inconsequential to us – but to a Super Eagle, with ultra-high-definition vision, it might seem an unimaginable failure. We take our experiences to be fully fleshed out only because we implicitly adopt our own level of fleshing out as all that needs to be specified.

Drawing on this idea of implicit perspectives, I want to explore another route to sparse spatial experience – one that will open the gateway to a radical rethinking of possible experiences, and (ultimately) to what’s imaginable. I’ll argue that spatial experiences can be radically sparse – not merely presenting a world with a few millimeters’ wiggle-room, but presenting a world in which there are spatial relations that are almost wholly underspecified. I won’t argue that such experiences are actual, but that they’re possible ... at least for the right sort of being.

Philosopher Dogs and Philosopher Owls

Dogs have an extraordinary sense of smell. Not only is their sense of smell thousands of times more acute than humans’, they are able to smell “in stereo”: Each nostril can be moved separately. And their brains keep track of which nostril an odor arrived at, granting them not only the ability to detect the presence/absence of smells, but to sense where they’re coming

Imagine a highly rational philosopher dog, capable of introspecting on the feel of their own experiences. They might well wonder “How could any creature have an olfactory experience where spatial relationships are omitted? Every instance of poop is located somewhere in space. How could an experience possibly fail to specify this? Surely it’s inconceivable."

This thought would clearly be misguided. We are just such creatures. We experience the smells of poop, of roses, of freshly baked bread. But these experiences typically don’t include spatial relationships. (At best, they simply represent these smells as being here.) These spatial details – details that a philosopher dog might think were essential to experiences – are simply not part of our experiences.

This is an extreme example. In the case of olfaction, one might think we simply don’t represent spatial relations at all. So perhaps it’s not surprising that we can have olfactory experiences that lack spatial details. It’s not as though all experiences must represent space. (My anxious experience don’t need to ‘say’ anything about space!) But examples from other sensory modalities show that it’s possible for experiences to be “underspecified” in a way that fixes some, but not all aspects of spatial location.

Suppose you hear a jackhammer, hammering away. Somewhere nearby, a baby starts to cry. For those with typical human hearing, the sounds of the baby and the jackhammer will seem to come from some direction or other. (Perhaps the jackhammering seems to be coming from your left, and the crying from your right.) But the precise locations of the sounds will not be included in the experience. How far are the two auditory stimuli from each other? Is one in front of or behind the other? Is the jackhammering coming from above the crying, or at a level with it? These details are left out of the experience. In fact, it seems so clear that our experience is silent on these details that it seems peculiar to say that the experience leaves them out – it’s alien to think that they could possibly be included.

But just as dogs might find it unintelligible for olfactory experiences to be silent on spatial relations, a barn owl might find it similarly unintelligible that our auditory experiences leave open aspects of spatial relationships. Barn owls have asymmetrically positioned ears. By comparing differences between the timing and intensities of sounds reaching each ear, their brains construct three-dimensional maps of the locations of sound sources. This enables barn owls to pinpoint the location of sounds to within 2-3 degrees of Once again, we can imagine the philosopher owl lamenting “How could any creature have an auditory experience where spatial relationships are underspecified? Every crying baby is located somewhere in space. How could an experience possibly fail to specify this? Surely it’s inconceivable.” But once again, we know that such experiences are possible, for we have such experiences. We hear the cry of a baby, the banging of hammers, our child calling to us from a crowded playground. Unlike our olfactory experiences, these experiences do seem to be laid out in space. But they don’t seem to present precise locations for any of the sounds.

It’s not that the sounds seem to be coming from precise locations, but we withhold judgment as to whether the appearances are accurate. I hear the sound loud and clear and to my right. It just doesn’t seem to be coming from any specific place to my right. It is not like the case of blur or vision in dim light, where the experience presents something fully fleshed out, but we judge it not to accurately reflect the world. The location of the sound seems to be omitted from the very experience itself.

Extrapolating from this: While some humans may find it unintelligible for there to be visual experiences that fail to fully specify spatial relationships, we should view ourselves as in the same position as the philosopher owl and the philosopher dog. Another creature could have visual experiences that were totally silent on spatial relationships, perhaps registering simply the presence/absence of a color. Another creature could have spatial relationships that included some spatial sensory information, but where it was – from our perspective – underspecified. We can no more imagine what such experiences would feel like than we can imagine what it would feel like to be a bat. But consideration of the limitations of our own perceptual systems in relation to those of other creatures should allow us to appreciate that another being could have them.

We think of ourselves as the paradigm of perception. But we are not. We are just one variety of experiencer among many. Appreciation of our limitations in relation to other experiencers with different perceptual systems can help us to open the door on the wide variety of possible experiences and experiencers there could be.

Why There is No Stopping Point

Another way we might gain insight into the range of possible experiences would be to discover general principles for inferring what experiences are possible from the experiences we know to be actual.

One such principle emerges from appreciation of the extent to which contingent psychological limitations, rooted in our physiology, influence what can be omitted from an experience. For example, the amount of sparseness in our peripheral color experiences is a function of the number of cones in the periphery of our retinas and the extent to which this information is winnowed down as it is passed along to our visual cortices. But the peripheral fields of our retinas could have had slightly more/less dense distributions of cones – resulting in slightly less/more sparse color experiences. The details are contingent on the details of the underlying physiology. And there are endless variations in the physiological possibilities.

Drawing on this, the following strikes me as a good principle:

More of the Same: Whenever there can be a degree of sparseness along a certain dimension of experience, there’s no principled barrier to there being more sparseness along that same

Suppose your experience leaves open hue within a certain range. Perhaps a feature of the experience is red-or-orange, but not any precise color in that range. Then there’s no principled barrier to there being an experience that leaves open the hue along a wider range, say, red-or13 orange-or-purple. Suppose your experience leaves open the location of a cry within a 30 degree range. Then there’s no principled barrier to there being an experience that leaves open the range of the cry within a 60 degree range. If our experiences can remain silent on whether the top dot is slightly to the right or left of the bottom dot, then some other creature’s experiences could leave open whether it was a bit more to the right or the left ... or a bit more … or even radically different right/left.

Why think this is a good principle? Suppose someone insists that there can be experiences allowing a degree of underspecification along some dimension, but that experiences allowing slightly more underspecification along that dimension are impossible. (Perceptual systems, they insist, could fail to specify locations within the range of 1-3mm ... But 3.01mm? Nope! That’s .01mm too much! That’s right out.) This would be bizarre. It would call out for an explanation. The trouble is that any place one could draw a line between a possible amount of underspecification and an impossible one will be arbitrary. And there simply aren’t arbitrary lines in what’s possible.

Combining the More of the Same principle with the varieties of sensory sparseness we’ve already encountered yields the possibility of some pretty wild experiences – experiences that we certainly cannot expect to have, but that we can nevertheless appreciate the possibility of. It suggests there could be creatures whose visual experiences depict trees and flowers and clouds that seem to exist in space ... but where none of these seem to have precise locations. Like human auditory experience, another creature might visually experience the cloud as “sort of up-ish”, the tree as “right-ish”, and the flowers as “behind me, I think”. Or, following on from the More of the Same principle, perhaps they all seem to be somewhere in space, but “nowhere in particular”!

The Triangle Berkeley Couldn’t Imagine

Enlightenment philosopher John Locke sought to explain how it was that we could think and talk about objects whose instances are so diverse. How can ‘dog’ pick out creatures as different as Golden Retrievers and Pomeranians? How can ‘red’ encompass scarlet, crimson, burgundy, and cherry? How can ‘triangle’ pick out figures varying so widely in angle size and side ratios? His answer was that we use a process of abstraction to construct a sort of mental representation that includes what is shared by all instances of the kind, while omitting what is particular to only some instances. Thus, the abstract general idea of redness would include what all instances of red share, while omitting everything that is not shared. The abstract general idea of a triangle would include what’s common to all (namely, being a three-sided closed figure) while omitting everything else (such as the sizes of the angles). And the abstract general idea of a dog would include what all dogs have in common (and what distinguishes them from, say, cats), while omitting anything that’s not universally shared.

It’s not entirely clear what Locke took ideas to be. Later Enlightenment philosopher George Berkeley took them to be something like mental images. And this led him to the conclusion that Lockean abstract general ideas were ridiculously, manifestly impossible. How are we to form a mental image that’s got what all triangles have in common, but lacks everything they don’t all share? Since some triangles are equilateral, some isosceles, and some scalene, this would mean forming a mental image of a triangle that’s neither equilateral nor isosceles nor scalene. As Berkeley writes,

I own, indeed, that those who pretend to the faculty of framing abstract general ideas do talk as if they had such an idea, which is, say they, the most abstract and general notion of all; that is, to me, the most incomprehensible of all

I am not going to argue that we can form such mental images. I’ll confess, I’m in the same position as Berkeley here. But I think that some possible creature could. I do not think that a mental image of a triangle that’s neither equilateral nor isosceles nor scalene is an absolute impossibility, but only an impossibility for creatures like us.

We’ve seen that there can be radically sparse spatial experiences. Now I’ll argue that we can take this a step further. If experiences can leave spatial relations open in this way, then there can be experiences of shapes with sparse boundaries.

Here is a quick (to my mind, too quick) argument to that effect: If relative locations of dots in an experience can be underspecified along the x-axis, then it should be possible for there to be an experience of three dots, where they all have fully specified locations along the y-axis, but where their positions along the x-axis is left open. And since a triangle is simply what you get when you have three lines intersecting such points, it follows that there could be an experience as of a triangle, where the relationship between the sides is similarly “left open”.

I think something like this is right. But it’s a bit too quick. In order for there to be a triangleexperience, the experience must include not only three points, but three straight lines, intersecting at these points. The challenge is to specify how an experience could remain silent on the relative locations of the points of intersection, while specifying that the lines between them (i) intersect and (ii) are straight.

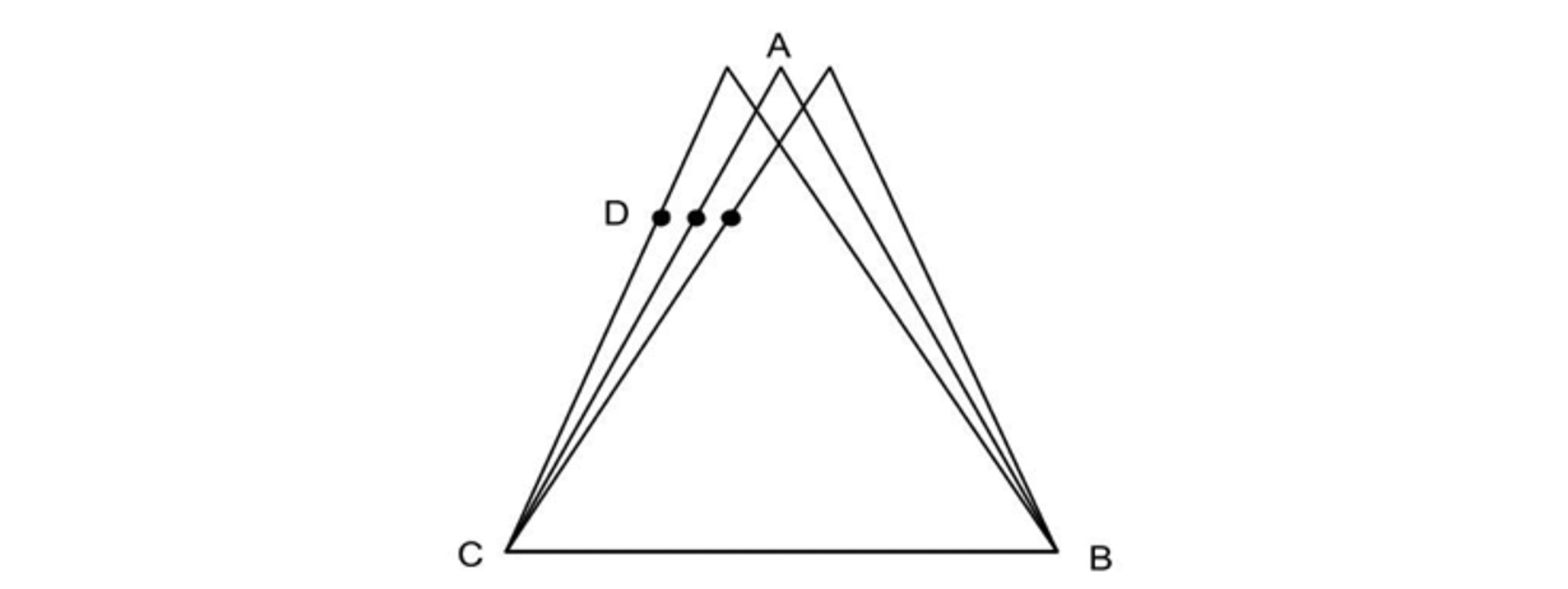

Consider this image representing a sparse triangle. I’ve depicted one of the vertices of the triangle (A) as being in a range of locations, as a way of illustrating that the experience does not precisely specify A’s location. The challenge is: how can it be specified that intermediate point D stands in the right relationship to vertices A and B, if the location of A is not precisely specified?

It’s intuitive to think about experiences by analogy to computer screens. A computer screen is made up of pixels, each of which is specified independently of each other – constructing images in a manner akin to a pointillist painting. If experiences were constructed in this way, it would be hard to see how sparse shapes could be possible. If the location of D were specified independently of each other ‘pixel’ of the experience, it could only stand in a fixed location relative to A and C if the locations of A and C were fixed. And in the sparse triangle, they are not.

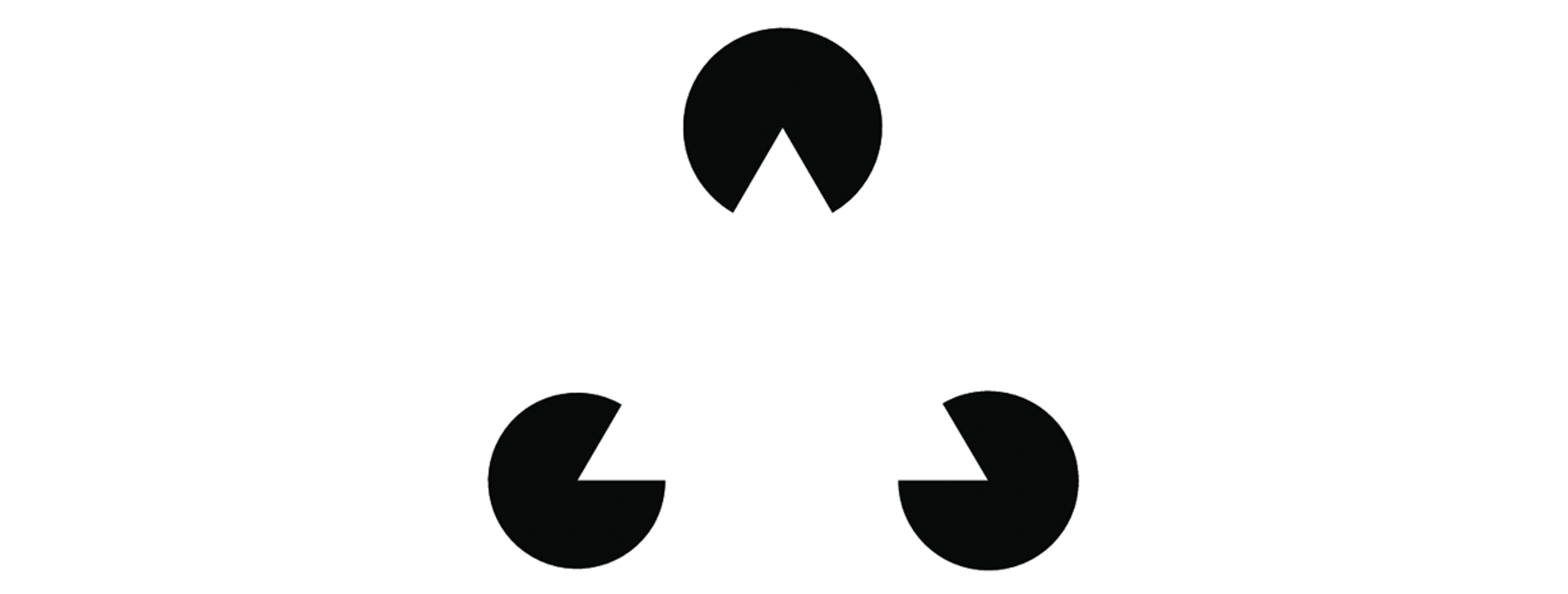

But should we think that experiences work like computer displays? Our brains certainly don’t work in this way. While the initial layer of the retina works in a pixelated way – taking in independent points of information about the environment – the way that our brains process this information integrates contextual information across progressively larger regions of the visual field. There are individual neurons within the visual cortex that are sensitive to the orientations of stimuli, e.g. whether a bar is oriented as ; there are individual neurons that are sensitive not only to the contrast between lightness and darkness, but to whether the brightness of a certain region is from the object or the ; there are neurons that respond to convex or concave curvature at particular points of the visual . Moreover, our perceptions of illusory figures such as the Kanizsa triangle – in which our brains construct shapes, edges, boundaries, and figureground distinctions that are not present in the ‘pixels’ – illustrate the effects of top-down processing and expectations on our visual .

So our brains don’t process information in a pixelated way. The structural features of our experiences don’t necessarily mirror the structure of the underlying neural processes. (Perhaps experiences work like computer displays, even though our brains don’t process them in this manner.) But considering the neurophysiology does offer another possible analogy for how experiences work. Perhaps the building blocks of experience aren’t little pixelated bits, but are something bigger: lines, curves, edges, contrasts. In short, perhaps our experiences work like our brains.

If this is right, the straightness (of line AC) could be a basic building block of the experience. Point D may simply be an abstraction from this straight line – an abstraction whose location is essentially tied to line AC. It is simply the point that occurs along AC at a certain degree of verticality. In this sense, its location can be underspecified (as falling in a certain range) while still having a determinate relation to both A and C. The figure can be both determinately a three sided, closed figure, made up of straight lines – and yet have underspecified vertices, and hence relations between the lengths of the sides and angles. We have ourselves a sparse triangle.

While the possibility of sparse shapes seems intuitively bizarre on its face, it actually fits with empirical data already alluded to: much as we saw with color, human subjects consciously see, but are unable to distinguish the shapes of, objects moving at high speeds. This is because when our brains process motion, they temporarily block the processing of spatial . So perhaps it is not as radical as it might first appear to think that we might (sometimes, briefly) have experiences as of sparse shapes.

Can Temporal Experiences Be Sparse?

If spatial experiences can be “sparse”, it’s natural to wonder whether there might also be temporally sparse experiences. Of all the varieties of sensory sparseness we’re considering, this one is by far the most strange – the argument for it, the most tentative.

I see the flash of lightning before I hear the crash of thunder... Or perhaps the lightning is close enough that I seem to hear the boom at the same moment as I see the flash. Knowing about the relative speeds of light and sound, my judgment about the order in which the events occurred may come apart from what my experience presents. But intuitively, our experiences always feel like their parts stand in fixed temporal relations to one another. Surely, I could never have an experience of a boom and of a flash ... and have there simply be no fact of the matter about whether they felt like they occurred together or one happened before the other.

But we’ve seen that many seemingly impossible experiences are, in fact, possible – for the right sort of creature. Could some creature have an experience of two events where A is experienced as before B, but where A isn’t any particular amount of time before B? Or, more radically, could there be an experience of two events occurring non-simultaneously, but where it was “left open” which event occurred first?

Answering these questions is especially tricky, as it depends on the correct account of the structure of temporal experiences – something there’s enormous disagreement about. So the case for sparse temporal experiences is less clear-cut than the previous cases. But following the schema I’ve already developed, I want to end with a quick case for thinking that there can be sparse temporal experiences – starting with experiences that we have and inferring the possibility of more radical sparseness.

As bizarre as it sounds, there are experimental results which suggest that we can have sparse temporal experiences... at least within a very narrow duration. If auditory stimuli are presented sufficiently close together (roughly 2-20ms), subjects can tell that the two stimuli occur nonsimultaneously, but cannot tell which stimulus occurred . Similar results have been found for other sensory modalities. In general, the threshold for detecting stimuli as non-simultaneous ranges from 2-3ms in the case of audition to 20ms in the case of vision. But we are unable to determine ordering for stimuli presented closer than 30ms . Taken at face value, this suggests that between the two ranges, we have experiences that present events as being nonsimultaneous, but where neither event is presented as being before the .

While we may only have such experiences on very short time scales, following the More of the Same principle, we can see that the amount of sparseness is a contingent feature of our psychology. If it’s possible for us to have experiences that are sparse in the range of 2-20ms, there’s no principled barrier to there being creatures who could experience sparseness between the ranges of 2-200ms ... or 2-20 seconds ... or far wilder things: thunder and lightning that aren’t experienced as simultaneous or sequential, a tennis match in which the order of events is underspecified, a conversation made up of meaningful words whose temporal order is left open.

The Alien Minds We’re About to Create

We don’t grasp the world directly. Perception is mediated by our sensory systems and cognitive limitations. It’s easy to forget that our window onto the world is but one possible window – to imagine that the world we find ourselves immersed in is the world, as opposed to one possible outlook – and so to forget that the world of the octopus, of the alien, of the AI may appear utterly unlike the world we take ourselves to inhabit.

If we confine ourselves to our own minds, framed by our own perceptual systems, we wind up with an impoverished sense of what sorts of experiences are possible. This is one reason why fiction and works of imagination are so powerful: they allow us to transcend our default way of looking at reality. Philosophy, working in tandem with neurobiology, has a similar potential to expand our perspective.

We may not have yet discovered conscious experiencers on other planets. But as we construct increasingly complex artificial minds, edging closer to plausible AI consciousness, it’s particularly timely to wonder what the mental lives of such beings might be like. We could blithely assume that they would be similar to our own; we could embrace radical epistemic limitations and throw up our hands in despair at coming to any understanding; or we could devise new ways of coming to appreciate the (to us) unimaginable: understanding our own limitations and position among possible experiencers, and using this to make inferences about what other beings might be like in relation to us.

The potential for radically sparse experiences may be particularly relevant to artificial experiencers. We should expect artificial experiencers to have immense potential for sparsity of experience, given that all of the parameters in their architecture are engineered and open to modification.

Much like human vision, traditional computer vision systems begin with pixel-level inputs and processing of low-level features like edges and color. They then have to transform this undifferentiated mass of raw data into a structured representation of the scene – something that breaks it down into objects with stable properties. To do this, computers use vectors that store information about various features that cluster in the scene. At a very abstract level, none of this is all that different from what our brains do in processing visual . The difference is how obviously contingent and readily modified the digital architecture is, based on starting architecture and training. A vector might specify that the object is {red, round, smooth} or simply that it’s {red, round} or simply that it’s . A computer might specify that the object is in the right-top quadrant of the scene, or simply in the right half. It’s almost trivial to see how a computer could have sparse representations. If these vectors that code for objects are sparse enough, the AI could potentially encode ‘human-shaped’ without coding any particular arrangement of features.

It’s not a huge surprise that information can be stored in ways that omit the details (“a man walks into a bar”). The surprise would be if AI could have sensory experiences of human shapes that aren’t any particular human form. While few think the AIs of 2025 are conscious, it is plausible that conscious AIs will be here well within our . Will future AI robots walking among us, with sensors for visual and auditory information, perceive the world as we do? Or will their perceptions be schematic and unfathomably sparse?

I’ve made the case for the possibility of experiences more sparse than our own. But – following the general principle that our own sensory systems and cognitive structure are not special among all possible sensory and cognitive systems – it may also be that there are experiences that are far richer than ours. Conscious AIs of the future may, instead, consider our sensory experiences schematic and impoverished. In either case, it’s plausible that the first alien minds we encounter will have not only vastly different qualitative experiences, but a different conception of space and time.

It’s time to burst our bubble. Experience can be wilder – far more schematic – than you thought. Colors with imprecise hues; shapes with imprecise boundaries; events without order. It may have been sufficient for 18th century philosophers to operate from the bubble of the human sensory system, but it no longer is. The future is closer than you think. And coming to grips with what the world may look like from the perspective of other minds will not only helps us to understand them, but may also help us to better grasp the space of what’s possible.

--

Bibliography

Ayer, A. J. The Foundations Of Empirical Knowledge. 1940. https://philpapers.org/rec/AYETFO.

Berkeley, George. Principles of Human Knowledge and Three Dialogues. Edited by H. Robinson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Block, Ned. “Consciousness, accessibility, and the mesh between psychology and neuroscience.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 30, no. 5-6 (2007): 481-499. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07002786.

Block, Ned. “Perceptual consciousness overflows cognitive access.” 2011. https://philpapers.org/rec/BLOPCO-2.

Butlin, Patrick, Robert Long, Eric Elmoznino, Yoshua Bengio, Jonathan Birch, Axel Constant, George Deane, Stephen M. Fleming, Chris Frith, Xu Ji, Ryota Kanai, Colin Klein, Grace Lindsay, Matthias Michel, Liad Mudrik, Megan A. K. Peters, Eric Schwitzgebel, Jonathan Simon, and Rufin VanRullen. “Consciousness in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Science of Consciousness.” arXiv:2308.08708 (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2308.08708.

Carr, Catherine E., and Jakob Christensen-Dalsgaard. “Sound localization strategies in three predators.” Brain, Behavior and Evolution 86, no. 1 (2015): 17-27. https://doi.org/10.1159/000435946.

Chalmers, David. “Could a Large Language Model Be Conscious?” Boston Review, August 9, 2023. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/could-a-large-language-model-beconscious/.

Curcio, Christine A., Kenneth R. Sloan, Robert E. Kalina, and Anita E. Hendrickson. “Human photoreceptor topography.” Journal of Comparative Neurology 292, no. 4 (1990): 497- 523. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902920402.

Dainton, Barry. “Temporal Consciousness > Some Relevant Empirical Findings (Psychology, Psychophysics, Neuroscience).” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition). Edited by Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archIves/fall2018/entries/consciousness-temporal/empiricalfindings. html.

“Dogs’ Dazzling Sense of Smell.” PBS NOVA. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/dogssense- of-smell/.

Fontenelle, M. de (Bernard Le Bovier de). Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/66559/pg66559-images.html.

Greff, Klaus, Sjoerd van Steenkiste, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. “On the Binding Problem in Artificial Neural Networks.” arXiv:2012.05208 (2020). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2012.05208.

Gross, Steven, and Jonathan Flombaum. “Does Perceptual Consciousness Overflow Cognitive Access? The Challenge from Probabilistic, Hierarchical Processes.” 2017. https://philpapers.org/rec/GRODPC.

Grush, Rick. “A plug for generic phenomenology.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 30, no. 5-6 (2007): 504-505. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07002841.

Hardin, C. L. “Frank talk about the colors of sense-data.” 1985. https://philpapers.org/rec/HARFTA.

Harvey, Ben M., and Serge O. Dumoulin. “The Relationship between Cortical Magnification Factor and Population Receptive Field Size in Human Visual Cortex: Constancies in Cortical Architecture.” Journal of Neuroscience 31, no. 38 (2011): 13604-13612. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2572-11.2011.

Hirsh, Ira J., and Carl E. Sherrick Jr. “Perceived order in different sense modalities.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 62, no. 5 (1961): 423-432. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045283.

Hubel, David H., and Torsten N. Wiesel. “Receptive fields of single neurones in the cat’s striate cortex.” The Journal of Physiology 148, no. 3 (1959): 574-591. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006308.

Kennedy, Gillian J., Harold S. Orbach, Gary E. Gordon, and Gunter Loffler. “Judging the shape of moving objects: Discriminating dynamic angles.” Journal of Vision 8, no. 13 (2008): 9.1-13. https://doi.org/10.1167/8.13.9.

Lee, Barry B., Paul R. Martin, and Ulrike Grünert. “Retinal connectivity and primate vision.” Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 29, no. 6 (2010): 622-639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.08.004.

Lee, Tai Sing, and Mitul Nguyen. “Dynamics of subjective contour formation in the early visual cortex.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98, no. 4 (2001): 1907-1911. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.98.4.1907.

Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding: In Two Volumes. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1894.

Nagel, Thomas. “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” The Philosophical Review 83, no. 4 (1974): 435- 450. https://doi.org/10.2307/2183914.

Pappalardo, Robert T., William B. McKinnon, and Krishan K. Khurana, eds. Europa. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1xp3wdw.

Pasupathy, Anitha, and Charles E. Connor. “Shape representation in area V4: Position-specific tuning for boundary conformation.” Journal of Neurophysiology 86, no. 5 (2001): 2505- 2519. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2505.

Stazicker, James. “Attention, Visual Consciousness and Indeterminacy.” Mind & Language 26, no. 2 (2011): 156-184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2011.01414.x. 25

Stazicker, James. “The Visual Presence of Determinable Properties.” In Perceptual Memory and Perceptual Imagination, edited by Fiona Macpherson and Fabian Dorsch. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. https://philpapers.org/rec/STATVP