"The Mind as a City: A Systems View of Consciousness" by Ian Reppel

Ian Reppel is an Argentina-based independent researcher and audio engineer with a PhD in theoretical physics and has spent nearly fifteen years working in technology across Europe and Latin America. He writes at ianreppel.org on quantum computing, machine learning, leadership, and psychology, with a particular interest in how technology, incentives, and leadership shape human agency. He is currently writing a book on ethical product psychology, examining how psychology can be used to help people flourish without defaulting to manipulation while still supporting profitable products that make a positive difference. He also runs his own music studio, Crow Oak.

The following essay by Ian was an honorable mention in the 2025 Berggruen Prize Essay Competition.

Consciousness is best understood as a system, not a single entity. Rather

than a single switch, it is an entire control panel with many switches and dials that can selectively disable or boost individual components or connections yielding different experiences we can probe in the lab. The systems view provides a cross-species perspective on consciousness, backed by philosophical traditions from across the globe, that also extends to artificial intelligence.

Consciousness reveals itself at the very edges: when we lose it, when we enter an altered state through meditation or drugs, or when we observe its behavioural effects in other species. If consciousness were a single switch, anæsthesia would turn it off and on again cleanly, and every species would have the same neural wiring. Neither is true. Human anæsthetics alter wakefulness, the contents of experience, self-monitoring, or the ability to report to various degrees depending on the drug, its dose, or the patient’s cortical state. That suggests a composite mechanism: a system of interacting subsystems with failure modes that can be induced selectively. Such a systems view is agnostic of the underlying neural architecture or layout, so it maps well to non-human brains, too. All that matters in the systems view are the functions that make experience at all possible.

While there is not a clear definition of that both scientists and philosophers can agree upon, one area where most can agree on a clear before and after, that is of consciousness and subsequent unconsciousness, even across species, is caused by . Anæsthesia and similar instances where people and animals lose consciousness in a controlled environment are ideal to study the nature of consciousness.

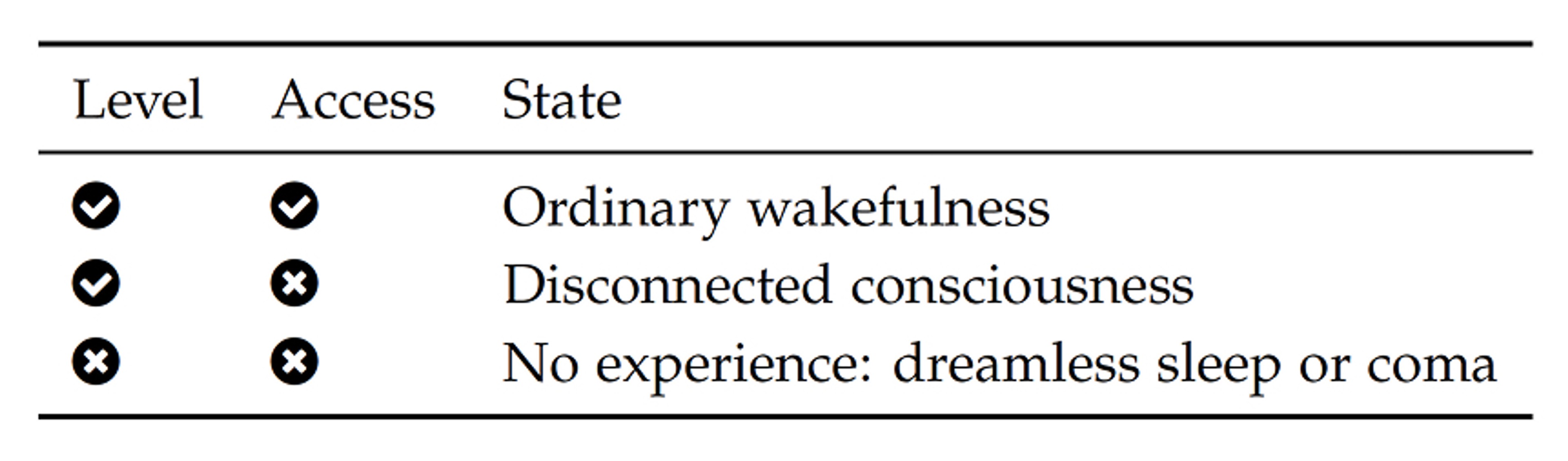

Clinical neurology defines levels of arousal and access to contents in terms of measurable dynamics and brain networks. While decry levels as a poor metaphor for consciousness that overlooks its multi-dimensional aspects, contest that view. Irrespective of each point of view, these concepts do indeed serve a clear clinical purpose. The systems view of consciousness offers mechanisms and a multi-dimensional view with levels and access that is also based on neural correlates of consciousness, yet entirely free from any theory of mind.

The edges of consciousness

Anæsthesia: now you see it, now you don’t

In the operating theatre, the anæsthesiologist is a magician. While the patient focuses on counting backwards from ten, they apply a few drops of a clear liquid, and, voilà, the patient’s consciousness disappears entirely, only to reappear after the main performance, the surgery, is done.

The magic trick looks identical in every act, yet that is the real illusion. Different anæsthetics dissociate level and access with different reproducible neural . Propofol produces frontal alpha rhythms that silence long-range frontoparietal communication. Ketamine preserves arousal while fracturing content and inhibiting the sense of self. Dexmedetomidine yields a sleep-like quiescence from which the patient can easily be aroused, often with dream-like reports upon prompting. There is therefore no single consciousness switch.

Clinical metrics such as the distinguish wakefulness from deep anæsthesia and dreamless sleep. PCI measures the brain’s capacity to coordinate across regions. It can even signal hidden capacity in . Anæsthetics such as propofol decrease the PCI, whereas ketamine keeps it steady or increases it. Psychedelics also boost the PCI.

Dream research shows that the back of the brain can build vivid scenes even when the frontal regions are not . With a pulse, the thalamus can temporarily restore intentional behaviour from deep anæsthesia in . Phrased differently, the brain can generate scenes without arousal, while arousal does not depend on any scene at all. Scene construction and arousal are separable parts of the same system.

Altered states of consciousness

We do not have to enter the hospital to lose consciousness: we do it every night when we fall asleep. During the non-REM stages, arousal and connectivity are lowered, whereas we have vivid dreams in REM sleep. Content generation is therefore decoupled from behavioural output or sensory input.

Traumatic brain injuries such as a concussion lead to a transient disconnection that impairs arousal, routing, or coordination, depending on the locus and severity. A short loss of consciousness often leads to the disruption of arousal pathways. Longer sequelæ cause network-level dysconnectivity. More severe disorders of consciousness (e.g. coma) can be evaluated with complexity measures, such as PCI. Interestingly, the EEGs of comatose patients often resemble those of people under general .

When a person faints, it is usually due to a lack of blood to organs. On an EEG it shows up as a slowing down, followed by a flattening, and eventually a re-emergence to normal patterns. In behavioural terms, a patient twitches and becomes unresponsive for a few seconds. This is a clear case of a failure of the level subsystem while the rest of the architecture remains intact.

Psychedelics and meditation

Psychedelics, such as LSD and psilocybin, increase brain activity and complexity and they tend to reduce the sense of . Mebufotenin even offers, in certain rare cases, a meditation-like trance of pure awareness without the self or the world .

Meditation does not raise the level so much as tune access by reducing self-chatter in line with the Buddhist concept of anattā, or lack of a self. Seasoned practitioners can often achieve higher levels of synchrony through gamma .

In imaging studies, we can see a clear pattern: the mind wanders, the lapse is noticed, attention is redirected, and quiet . Psychedelics achieve pretty much the same, albeit temporarily, through biochemistry.

These examples at the edges of consciousness demonstrate that the same outward ‘lights off’ can arise via different component failures. Some drugs target arousal, while others affect routing or coordination. Conversely, ‘lights on’ can return through the restoration of a single or select few pathways. In that sense, consciousness behaves like a multi-component control system with bidirectional couplings (to and from the environment), feedback loops, and characteristic failure modes.

What we have so far seen is that consciousness is fragile and it can be disabled through level and access subsystems with different outcomes. These are summarized in the table below.

Consciousness: more than the sum of its parts

Some of what humans do is accomplished without consciousness. Consider the jazz musician submerged in improvisation, whose fingers find the right notes before any conscious thought could guide them. Or consider the common experience of ‘highway hypnosis’ in which one arrives at a familiar destination with no memory of the journey, having navigated complex traffic unconsciously. These are not trivial functions; they are feats of incredible computational complexity, run by fast, efficient, and entirely nonphenomenal systems. As we master a skill, its execution migrates from the slow, energy-intensive prefrontal cortex to the lightning-fast, automated machinery of the basal ganglia and cerebellum. It is a triumph of evolutionary efficiency.

Think of the brain as a metropolis at night. Neurons zip across the city like vehicles; it is busy even when we think the city sleeps. Consciousness is a motion picture narrated by the self that casts a spotlight onto a neighbourhood, a street corner, or the entire skyline. It is not factual newsreel footage, but a deeply personal snapshot of life in the metropolis that requires the various neighbourhoods to be powered up and connected through arterial roads and boulevards. The ‘now’ is a clever reconstruction, an audiovisual illusion of things as they were mere moments ago. It is an illusion so seamless no one ever notices it.

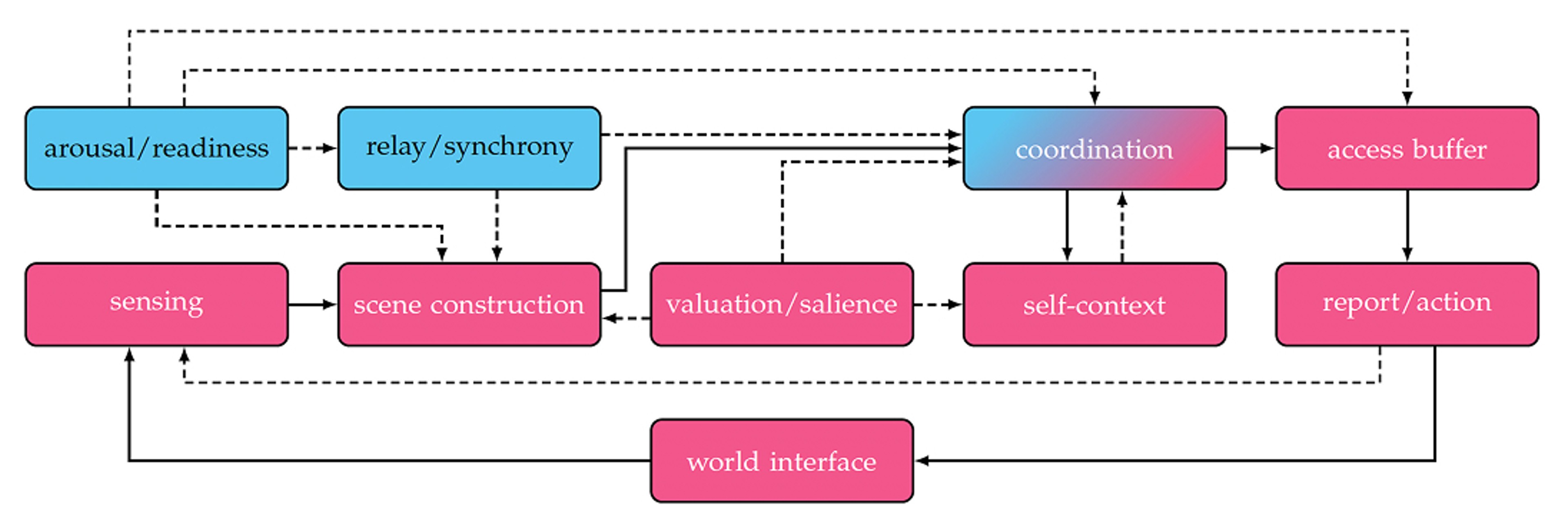

In this metaphor, level is the power grid. When we are awake, the city is brightly illuminated and busy. General anæsthesia is the equivalent of a city-wide blackout. Non-REM sleep matches a curfew, in which the lights may be on, but cross-town traffic is sparse. Access is the city’s news feed. When information is syndicated, it becomes available to many parts of the metropolis. Consciousness is not a single entity or located in a single spot. It is about functions and their connections. In Figure 1, the components of the consciousness system are shown. We shall explore the various components and links and tie them to the city-at-night metaphor to illustrate the purpose of each. It is based on insights from the edges of consciousness in humans and non-human animals; it is not tied to any single neural architecture.

Arousal/readiness

The arousal/readiness component is the control room of the city’s power grid. When the voltage is high, the nightlife is vibrant and consciousness’ movie can capture whatever moment is of interest. When the voltage drops, entire blocks go dim and the narrator’s voice goes quiet. It can also raise or lower the brightness across neighbourhoods. Without arousal/readiness, people end up in sleeplike states, such as fainting spells or even a coma.

Anatomically, arousal is handled by the brainstem and hypothalamus by means of orexin, which regulates arousal, wakefulness, and appetite. Norepinephrine sets the voltage levels across the entire city by focusing attention, while acetylcholine boosts incoming sensory transmissions.

In animals, we find similar brain structures. A single mutation in an orexin receptor causes narcolepsy in dogs, which shows that turning a single chemical key can switch off the lights in the dog . Cephalopods cycle between quiet and active sleep that resembles REM, though with an entirely different neural .

Relay/synchrony

Relay and synchrony are the traffic rules that coordinate remote regions to keep traffic flowing smoothly across the city. It is the precise timing that matters, not the magnitude or density of traffic . In humans, the thalamus acts as the brain’s clock. Failure in relay/synchrony leads to dissociation as in anæsthesia or ignition failures, in which a local representation never makes it outside the own neighbourhood.

Even though birds lack a laminated neocortex, corvids exhibit the mind as a city: a systems view of consciousness 5 responses that mirror subjective detection, which implies a relay-like coordination in the . While octopuses lack a mammalian thalamus, they show coordinated transitions: as they flip between active and quiet sleep modes, several brain regions’ rhythms alternate as if the octopus’ city re-timed all the traffic lights at once to reroute neural traffic. The implementations are all different, but the function is the same.

Coordination

While relay/synchrony enables the city to coordinate traffic across areas without gridlock, coordination is the actual infrastructure to do that: roads, signs, and traffic lights. In humans, the capacity to coordinate reflects large-scale dynamics right between order and disorder, the sweet spot between gridlock and chaotic traffic where neighbourhoods can synchronize when needed and desynchronize to explore. Evidence suggests that the cortex hovers near this criticality point to maximize flexibility in .

Various functional networks exist in the human brain that require long-range communication. For instance, the default mode network (DMN) is active during introspection, daydreaming, and memory recall. Dogs have an equivalent network as well as sensorimotor and auditory . The avian brain also has the hardware necessary for coordination, which proves that a cortex is not .

Sensing

Street cameras and microphones furnish the city’s live feed. Sensing supplies the streams that consciousness draws upon for the scenes in its movie of brain city. In the cortex, the primary sensory areas encode features for use in the entire city. When the data feed is offline, the city runs on guesses. That data feed combined with our expectations (i.e. priors) is used to forecast the ‘now.’ This now-casting improves sensory representations of the world . The brain anticipates and corrects its now-casts as more sensory data arrives. Integration of sensory data feeds is common in all animals.

In humans and macaques, gamma waves carry sensory data forward while alpha and beta waves feed it back to shape the . In mice, similar band-specific feed-forward and feed-backward mechanisms for sensory information . Most of sensing is performed in the primary sensory cortices, insula, and brainstem nuclei.

Scene construction

Scene construction is done by the art department, specifically the set designer and continuity editor. They use the control room’s displays and loudspeakers to build a coherent shot from partial footage by filling in gaps or painting over seams so the experience feels seamless. A posterior ‘hot zone’ that crosses the parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes is the conductor for dreams in the human . The orchestra, so to speak, is shared among many regions, such as the limbic system (emotions), the hippocampus (memories), temporal lobe (visuals), and frontal cortex, yet notably without the logical prefrontal cortex. Without the conductor, the orchestra does not play; the conductor alone is not sufficient to dream either. When scene construction fails, it can lead to dissociation of content that feels fragmented.

Scene construction is ultimately powered by prediction: the ‘now’ is the brain’s best guess of it, because sensory data is always delayed and only up to a few hundred milliseconds later available for conscious . Without prediction, we would bump into each door frame, get hit by every ball, or crash a car into where it was a split-second .

Cuttlefish have episodic that combines the what, where, and when of events in the past with even the possibility of false due to errors in scene (re-)construction: their ‘now’ is stitched together after the fact rather than recorded live.

Access buffer

The access buffer is the jumbotron in the central square: when information hits the screen, the entire city can coordinate around it, as otherwise the footage remains local. Whatever is shown on it is only available briefly and the amount of content that can be displayed is limited, so it is a bit like a scratchpad. Experience without the access buffer leads to disconnected consciousness.

The access buffer is distributed across the prefrontal and parietal cortices, supported by sensory regions. Sedatives decrease the access buffer’s capacity, so that ultimately awareness cannot reach report/action. A similar structure can be found in and mammals.

Valuation/salience

Valuation and salience set the city’s priorities right now, for which the salience network is primarily responsible in humans. The component also acts as the switchboard for attention, as it patches communication between relevant regions as needed. In mammals, homologous networks have been observed. and set priorities via different circuits that are linked to motivation and action selection. A failure in this component leads to either apathy or extreme distractibility due to mis-prioritized contents.

Self-context

Consciousness’ film producer is the self-context, powered by the default mode network, for which homologues exist in . With the aid of the valuation/salience component, it also narrates the motion picture. In case of failure of the self-context, depersonalization, out-of-body illusions, loss of agency, or anosognosia-like dissociations the mind as a city: a systems view of consciousness can occur. Internally, the self-context offers priors that bias internal decisions, whereas externally it is a communication interface.

This is supported by various philosophical traditions. Ubuntu’s maxim ‘I am because we are’ captures Menkiti’s conviction that personhood is constituted through communal life rather than conferred at . Hegel and Mead too believed that the self arises through social interactions and mutual . In social species, a stable narrative self improves predictability and therefore trust.

Report/action

Avicenna imagined a man suspended in air and cut off from all sensations, not unlike someone inside a modern sensory deprivation tank. Such a floating man would still know that he exists, because self-awareness does not depend on the body or the world. It is a thought experiment designed to home in on the minimal conditions for consciousness, in which the self-context is isolated from all interfaces. It presupposes arousal/readiness to sustain awareness, but self-awareness survives even when sensing and report/action are stripped away, though relay/synchrony and coordination are, in the systems view, still needed.

Report/action externalizes the scenes that have been selected in terms of actions, decisions, or communication. Language is a very efficient means, though need not be the only one, especially across species. In humans the prefrontal and premotor cortices translate accessible content into speech and motion, respectively. When there is no report/action, people are locked in themselves as if paralysed: they experience and are aware of their experiences, but they cannot act on them or talk about them. The ability to produce embodied actions from conscious content is present in all animals.

World interface

The world interface is the city’s connection to and from the outside world with sensors, actuators, and environmental feedback. Inner scenes can play in dreams across many species even though motor output is absent.

Connections

The connections can be subdivided into content and modulatory links. The former carry information payloads from one component to another, whereas the latter only alter what content is promoted or suppressed across regions through neuromodulators. Content moves on millisecond spikes, whereas neuromodulators act through biochemical diffusion processes. These are sometimes referred to as drivers and .

When we change modulation without affecting contents as in anæsthesia, we lower arousal and long-range communication in the brain. Likewise, when we alter the contents (e.g. binocular rivalry) while keeping the modulation the same, attention boosts the response of neurons that are tuned to the attended feature or location, thus sharpening the contrast without adding novel content. Similarly, when we stimulate the motor area in monkeys without any change in arousal, they can ‘see’ the . These demonstrate that the content/modulation split matches different dissociation mechanisms in the brains of various species.

Nishida argued that experience without a self is not only possible but pure: it occurs before the split between subject and object, which is exactly the link between scene construction and coordination

From the world interface through sensing, scene construction, coordination, the access buffer, and report/action back to the world interface, the links carry content that stitches frames into a consistent audiovisual experience coloured by the self-context. It consists of the entire conscious feedback loop from sensory inputs to outputs, such as movement and speech.

The content link from coordination to the self-context updates the self model, and the modulatory link back biases information in the coordination component to be about the self. The latter does not carry new content.

There is also a link back from the world interface to report/action, although such reflexes are obviously not part of the consciousness system itself as they bypass it entirely.

From arousal/readiness to everything else, the connections are neuromodulatory and involve norepinephrine, acetylcholine, histamine, serotonin, dopamine, and orexin.

The links from valuation/salience are also modulatory, as it prioritizes content for scene construction (amygdala and insula), the self-context (cingulate cortex), and coordination (salience network). This is mostly handled by reward systems.

Report/action and sensing are connected by means of an efference copy, which is the internal duplicate of motion signals for comparison of sensory information to check whether the actual movement matches the desired one. Since no new content is fed back, it is modulatory.

Scene construction is modulated through relaying and synchronization. The same is true for coordination that depends on exact timings across brain regions.

Predictions

The systems view offers falsifiable predictions. For instance, specific thalamo-cortical stimulation that restores relay/synchrony without raising arousal ought to restore report/action while under dexmedetomidine sedation, which disables the arousal/readiness component. In macaques, such stimulation awakens the cortex within . Deep-brain stimulation of the central thalamus also improves responsiveness in humans with chronic disorders of consciousness. The idea is as follows: under stable anæsthesia, apply a centrallateral stimulation and check whether coherent report transiently returns. If it does indeed, relay/synchrony are as separate as the systems view claims; if not, it is not an independent lever.

We already know that we can zap the cortex and listen to the electrical echo, which is the essence of the PCI. What is missing is a sequential experiment within the same subjects: one session titrated to unresponsiveness with propofol and another with ketamine. In both cases, the PCI and directed connectivity (i.e. who drives whom) are to be recorded with a structured debrief on recovery about the stability of self and mental scene. If ketamine yields a high PCI with an unstable self while propofol yields a low PCI with simple or absent content in the same subjects, the systems view holds as there are two independent knobs to control consciousness through anæsthesia.

Furthermore, a patch on the back of the cortex tracks whether people are dreaming. When it lights up in the right way, vivid reports follow upon awakening, even if the rest of the brain appears quiet. So, if that patch aids in building content, then a brief zap during non-REM sleep ought to shift people towards mentation without a surge in arousal. Once awake, we must collect the report. If we can selectively turn up scene construction while the level stays low, the systems view holds. If not, it suggests that content and level are less separable than the systems view claims.

Similar predictions and experiments can be designed to verify whether each component in the systems view is truly independent from the others. Likewise, we can construct experiments that check similar component-wise independence across species. That way, we can gradually refine the model and arrive at a minimal set of components required for consciousness in biological systems.

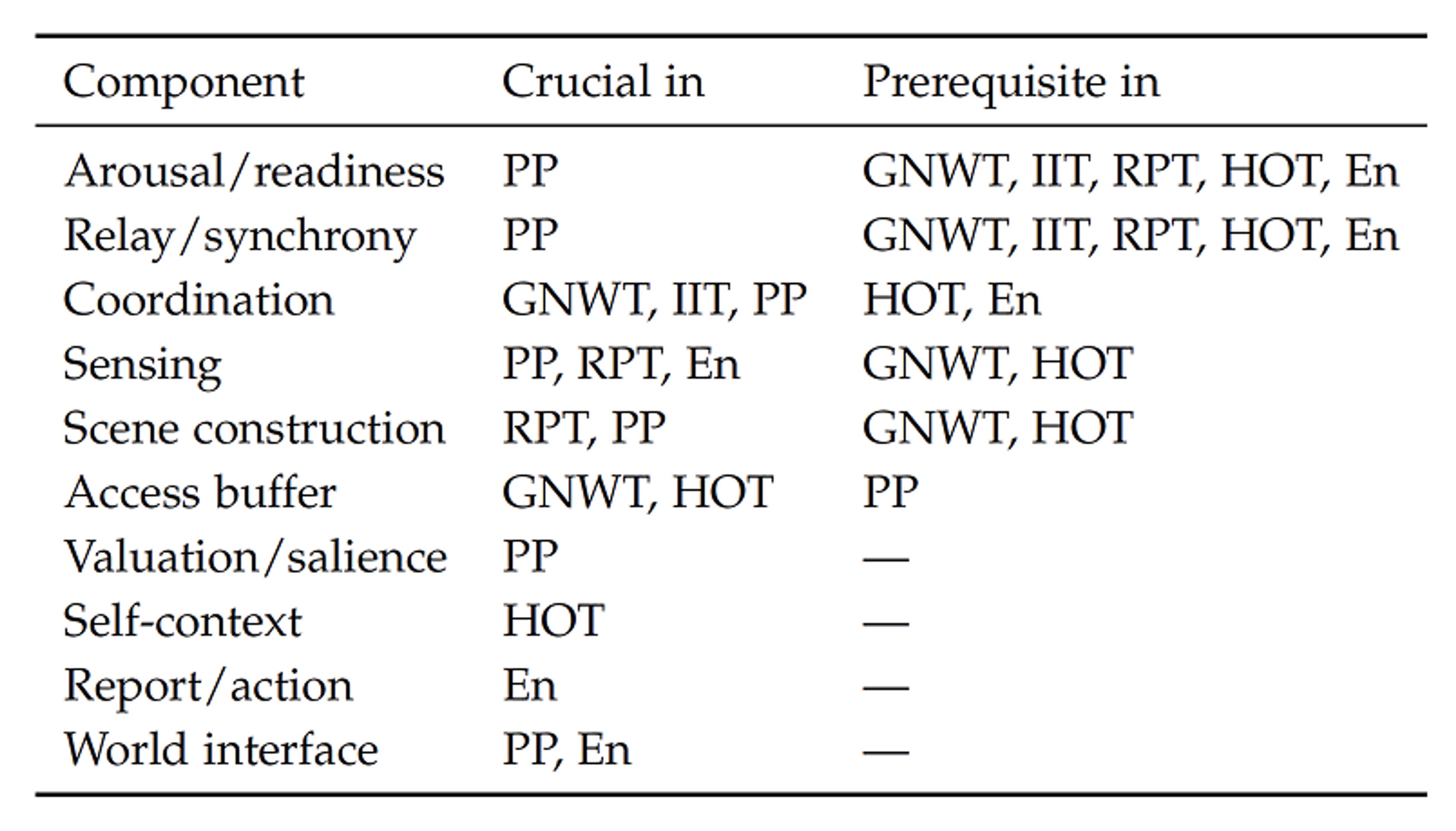

Theories of mind and the systems view of consciousness

The systems view presented here unifies the clinical level and cognitive access that is based on insights from the edges of consciousness and various species. It explains why anæsthetics have different signatures rather than a single signature. We can even map concepts from various leading theories of to the systems view, upon which theories of mind stop being rivals and instead own a particular component, as shown in Table 2.

According to the Global Neuronal Workspace Theory (GNWT), consciousness happens when a representation ‘ignites’ a long-range cortical network, so it becomes available for report, actions, and memory. The key region for GNWT is the prefrontal cortex.

Integrated Information Theory (IIT) proposes that consciousness arises from information integration. The quantity F measures the degree to which information is integrated, for which the posterior hot zone plays a key role. To have a non-zero value of F, all constituent matter must contain trace elements of consciousness, which leads to panpsychism as a prerequisite.

A recent experiment pitted GNWT against IIT and found that neither explains consciousness . Particularly, the researchers found that consciousness arises even without sustained synchronization in the posterior cortex and without an ignition in the prefrontal cortex. Instead, we can map GNWT to the access buffer and both GNWT and IIT to coordination, as they both require broadcast or integration (i.e. coordination).

In Predictive processing (PP), the brain is a prediction machine: it generates models of the world and updates these by minimizing a prediction error, which is the difference between its guesses and sensory inputs. The entire control system in PP requires scene construction to generate predictions biased by valuation/salience, arousal/readiness to be able to generate and improve predictions, relay/synchrony for fast communication, coordination for inference over sensorimotor information, and the world interface to close the loop.

Recurrent Processing Theory (RPT) says that feedback loops from sensory areas to higher-level cortical areas give rise to consciousness in thalamo-cortical loops. Features from sensory data are unconsciously extracted (e.g. shapes, colours, and motion), for which feedback from higher-level regions provides context (e.g. a face) that is again used to refine expectations in lower-level areas. Local recurrent processing is sufficient for consciousness, so that the access buffer and access consciousness through the prefrontal cortex are merely add-ons for report/action, not consciousness as a whole.

With Higher-Order Thought (HOT) theory, a mental state becomes conscious when an individual has a suitable higher-order representation of being in that state. Consciousness is thus meta-awareness. The self-context is the seat of consciousness in HOT, which is powered by the access buffer’s higher-order thoughts. Because the systems view talks about components and connections rather than specific anatomical locations, HOT can be mapped, even though it does not deal with a specific implementation in humans or other animals.

Enactivism (En) posits that all cognition is embodied and thus shaped by sensorimotor actions: animals experience the world by exploring it and understanding the sensorimotor patterns their interactions generate. The world interface and report/action are therefore essential to its operation.

Artificial consciousness?

The systems view offers a blueprint for consciousness in silico based on what we know of it in vivo. It is the specific components, their functions, and their connections that give rise to consciousness, not the neural architecture or substrate; there is no magical separation between carbon and silicon. As such, artificial consciousness is a distinct possibility and falsifiable prediction.

Large generative models display rich scene construction, but they have no intrinsic arousal/readiness tied to a body: when switched off, they do not exhibit activity such as dreams. Their ‘sensing’ is optional. Report is their only output channel with no sense of self or valuation that matters to its integrity. In the case of robots, ‘sensing‘ is linked to an actual body and they can act as well as report, though artificial embodied experiences powered by multimodal models, such as Google’s RT-X Platform, are still .

A possible objection to consciousness as an emergent phenomenon is often voiced by proponents of IIT: how can consciousness arise from non-conscious matter? There is actually nothing mystical about emergent properties in systems. The motion of atoms and molecules generates heat, even though no atom or molecule has a ‘temperature’ as such. In a similar manner, traffic jams happen because of many cars acting and reacting in a dynamic system, even though no single car has a ‘traffic jamminess’ property. Traffic jams come about through interactions, inherent bottlenecks, and flow patterns, where a phase transition occurs that separates a smooth traffic flow from gridlock. Consciousness is, in the systems view, no more mysterious as system behaviour than traffic jams or heat.

Philosophical implications

The systems view offers a unique perspective on a classic puzzle, Theseus’ ship, which asks whether a ship that has every plank replaced one at a time remains the same ship. In minds, the analogue is a gradual neural replacement, which is intimately connected to the question of identity. All that matters in the systems view are the components’ functions and their interactions, not the material itself. So, as long as the planks are nailed together in the same way and they perform the same function as before, it is indeed the same ship. If we replaced all neurons with synthetic ones, but maintained the original connections, functions, and links, the mind would still be the same one.

The systems view matches the ‘fading and dancing qualia’ thought experiment: if qualia could drift (i.e. vanish or shift) without alterations to function, absurd transitions where reports and actions continue as before while the inner movie conflicts are . Since that is deemed implausible, a functional rather than material organization of consciousness is more reasonable.

The systems view turns Theseus’ ship from a paradox into an engineering challenge: with the right tools we can switch consciousness on or off and perhaps even engineer it into existence in artificial life forms. In that sense, Descartes’ evil demon is nothing but a neurosurgeon who can manipulate a patient’s mind through deep brain stimulation.

Philosophical zombies are functionally perfect facsimiles with no experience. The systems view refines the thought experiment, because it requires us to specify at which level functional duplication is performed. If it is done at the level of components and their connections, the systems view demotes philosophical zombies to unfalsifiable stipulations. Moreover, by probing the edges of consciousness, we can look for specific connections among components we can break (with anæsthetics) or remake (with stimulation) on demand. If zombies are possible, they are only so in a way that shows all the clinical signatures of consciousness yet lacks it altogether.

Narrowing the hard problem

The systems view does not solve the hard problem, but it narrows it. Instead of asking why matter yields experience, it asks which specific causal links yield which families of experience. It does not settle all metaphysics, but it fences it in. The hard/easy divide and the explanatory gap still stand. What changes is where the gap is located and how narrow we can make it.

First, the problem of phenomenal character becomes empirical. The self-context is a dedicated node within the systems view that monitors and models what the rest of the system is doing. Attention-schema theory and metacognitive models (e.g. HOT) purport that the brain maintains a simplified sketch of its own access and control. When we edit that sketch, people change what they report about awareness even when early sensory coding remains intact. This reframes the debate around qualia. At least part of the ineffable ‘feel’ is the output of a self-monitor that can be tweaked and tested. Any theory of mind must survive these reversible, component-specific interventions.

Second, once experience is tied to specific components, claims that phenomenal character floats freely above the consciousness system must account for why the same perturbations predictably erase or restore both signatures and reports.

What is left of the hard problem is to explain why a particular state has a particular type of felt presence and why the system insists there is something beyond the obvious.

Consciousness as a golden lion

Consciousness as a system is not a novel idea. Fazang’s golden lion teaches that the matter may be the same, but the relationships among the matter are what turn gold into a lion. Consciousness is the golden lion: it may be made out of neurons, dendrites, and axons, but it is the way these are wired up that gives rise to consciousness.

We even find echoes of the systems view among the Aztecs. In Nahua philosophy, each person is animated by three forces: tonalli (vigour), teyolía (identity, memory, knowledge), and ihíyotl . It was believed that tonalli could leave the body during sleep, which maps cleanly to arousal/readiness. Valuation/salience is equivalent to ihíyotl, whereas teyolía aligns itself roughly with scene construction, coordination, and the self-context, which together provide a coherent yet biased view of the world and the person in it.

Philosophical traditions from east and west, north and south, have all espoused consciousness as a system for centuries, though not in those words or with the specific components and connections as proposed here. It does suggest a convergent, systems-level understanding of the mind across cultures.

The systems view unpacks consciousness into a set of interacting functions whose disruptions map to measurable phenomena across drugs, injuries, and species. It shows why level and access are a useful clinical shorthand. More importantly, it reframes cross-species arguments on consciousness; it is about the components and connections, not a cortex.

When we view consciousness not as a ghost in the machine but as the dynamic, functional organization of the machine itself, we gain five benefits. First, it is independent of the neural architecture or its substrate, so that it applies across species and even to artificial life forms. Second, it constrains philosophy. Any theory that denies a systems view must explain how individual components can be disabled selectively yet lead to different experiences. As such, it narrows the hard problem though it does not eliminate it. Third, various theories of mind can be mapped to the components of the system, which reduces rivalry and focuses instead on the merits in each idea. Fourth, we can ask better questions about the inner lives of animals and the ethical implications thereof. The Cambridge and New York declarations on consciousness are already a step in that . Like the systems view, these are informed by the latest science and philosophy. Fifth, it explains why current AIs are not imbued with consciousness while offering a blueprint for such artificial consciousness.

While we still do not know the minimal set of components and connections needed to generate artificial consciousness in the lab, we do know enough to stop arguing about a single switch of consciousness and instead focus on the entire control panel. The task ahead is therefore to chart the wiring of the entire city of the mind.

--

References

[1] Adeeti Aggarwal, Connor Brennan, Jennifer Luo, Helen Chung, Diego Contreras, Max B. Kelz and Alex Proekt, ‘Visual Evoked Feedforward–Feedback Traveling Waves Organize Neural Activity across the Cortical Hierarchy in Mice’, Nature Communications 13, 4754 (2022).

[2] Kristin Andrews, Jonathan Birch and Jeff Sebo, ‘Evaluating Animal Consciousness’, Science 387, 822–824 (2025).

[3] Kristin Andrews, Jonathan Birch, Jeff Sebo and Toby Sims, The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness, New York University, Apr. 2024.

[4] Jessica R. Andrews-Hanna, Jonathan Smallwood and R. Nathan Spreng, ‘The Default Network and Self-Generated Thought: Component Processes, Dynamic Control, and Clinical Relevance’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1316, 29–52 (2014).

[5] Alfredo López Austin, The Human Body in the Mexica Worldview, edited by Deborah L. Nichols and Enrique Rodríguez-Alegría, Vol. 1 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2016).

[6] Tim Bayne, Jakob Hohwy and Adrian M. Owen, ‘Are There Levels of Consciousness?’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20, 405–413 (2016).

[7] Emery N. Brown, Ralph Lydic and Nicholas D. Schiff, ‘General Anesthesia, Sleep, and Coma’, New England Journal of Medicine 363, 2638–2650 (2010).

[8] Robin Carhart-Harris and K. J. Friston, ‘REBUS and the Anarchic Brain: Toward a Unified Model of the Brain Action of Psychedelics’, Pharmacological Reviews 71, 316–344 (2019).

[9] Adenauer Casali, Olivia Gosseries, Mario Rosanova, Mélanie Boly, Simone Sarasso, Karina Casali, Silvia Casarotto, Marie-Aurélie Bruno, Steven Laureys, Giulio Tononi et al., ‘A Theoretically Based Index of Consciousness Independent of Sensory Processing and Behavior’, Science Translational Medicine 5,

10.1126/scitranslmed.3006294 (2013).

[10] Silvia Casarotto, Angela Comanducci, Mario Rosanova, Simone Sarasso, Matteo Fecchio, Martino Napolitani, Andrea Pigorini, Adenauer G. Casali, Pietro D. Trimarchi, Melanie Boly et al., ‘Stratification of Unresponsive Patients by an Independently Validated Index of Brain Complexity’, Annals of Neurology 80, 718–729 (2016).

[11] David J. Chalmers, ‘Absent Qualia, Fading Qualia, Dancing Qualia’, Conscious Experience, 309–328 (1995).

[12] Lixiang Chen, Radoslaw M. Cichy and Daniel Kaiser, ‘Alpha-Frequency Feedback to Early Visual Cortex Orchestrates Coherent Naturalistic Vision’, Science Advances 9, eadi2321 (2023).

[13] Luca Cocchi, Leonardo L. Gollo, Andrew Zalesky and Michael Breakspear, ‘Criticality in the Brain: A Synthesis of Neurobiology, Models and Cognition’, Progress in Neurobiology 158, 132–152 (2017).

[14] Cogitate Consortium, Oscar Ferrante, Urszula Gorska-Klimowska, Simon Henin, Rony Hirschhorn, Aya Khalaf, Alex Lepauvre, Ling Liu, David Richter, Yamil Vidal et al., ‘Adversarial Testing of Global Neuronal Workspace and Integrated Information Theories of Consciousness’, Nature 642, 133–142 (2025).

[15] Antoine Del Cul, Sylvain Baillet and Stanislas Dehaene, ‘Brain Dynamics Underlying the Nonlinear Threshold for Access to Consciousness’, PLOS Biology 5, e260 (2007).

[16] Eric Drebitz, Lukas-Paul Rausch and Andreas K. Kreiter, ‘Gamma-Band Synchronization between Neurons in the Visual Cortex Is Causal for Effective Information Processing and Behavior’, Nature Communications 16, 7380 (2025).

[17] Marco Fuscà, Felix Siebenhühner, Sheng H. Wang, Vladislav Myrov, Gabriele Arnulfo, Lino Nobili, J. Matias Palva and Satu Palva, ‘Brain Criticality Predicts Individual Levels of Inter-Areal Synchronization in Human Electrophysiological Data’, Nature Communications 14, 4736 (2023).

[18] Samuel D. Gale and David J. Perkel, ‘Anatomy of a Songbird Basal Ganglia Circuit Essential for Vocal Learning and Plasticity’, Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy 39, 124 (2010).

[19] James J Gattuso, Daniel Perkins, Simon Ruffell, Andrew J Lawrence, Daniel Hoyer, Laura H Jacobson, Christopher Timmermann, David Castle, Susan L Rossell, Luke A Downey et al., ‘Default Mode Network Modulation by Psychedelics: A Systematic Review’, International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 26, 155–188 (2022).

[20] Wendy Hasenkamp, Christine D. Wilson-Mendenhall, Erica Duncan and Lawrence W. Barsalou, ‘Mind Wandering and Attention during Focused Meditation: A Fine-Grained Temporal Analysis of Fluctuating Cognitive States’, NeuroImage, Neuroergonomics: The Human Brain in Action and at Work 59, 750– 760 (2012).

[21] Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2013).

[22] Christelle Jozet-Alves, Marion Bertin and Nicola S. Clayton, ‘Evidence of Episodic-like Memory in Cuttlefish’, Current Biology 23, R1033–r1035 (2013).

[23] Peter Kok, Janneke F. M. Jehee and Floris P. de Lange, ‘Less Is More: Expectation Sharpens Representations in the Primary Visual Cortex’, Neuron 75, 265–270 (2012).

[24] Robert Lawrence Kuhn, ‘A Landscape of Consciousness: Toward a Taxonomy of Explanations and Implications’, Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 190, 28–169 (2024).

[25] Andrew Lee, ‘Degrees of Consciousness’, Noûs 57, 553–575 (2023).

[26] Mariana Lenharo, ‘The Consciousness Wars: Can Scientists Ever Agree on How the Mind Works?’, Nature 625, 438–440 (2024).

[27] L. Lin, J. Faraco, R. Li, H. Kadotani, W. Rogers, X. Lin, X. Qiu, P. J. de Jong, S. Nishino and E. Mignot, ‘The Sleep Disorder Canine Narcolepsy Is Caused by a Mutation in the Hypocretin (Orexin) Receptor 2 Gene’, Cell 98, 365–376 (1999).

[28] Philip Low, Jaak Panksepp, Diana Reiss, David Edelman, Bruno Van Swinderen and Christof Koch, The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, Francis Crick Memorial Conference on Consciousness in Human and Non-Human Animals, Cambridge, UK, July 2012.

[29] Antoine Lutz, Lawrence L. Greischar, Nancy B. Rawlings, Matthieu Ricard and Richard J. Davidson, ‘Long-Term Meditators Self-Induce High-Amplitude Gamma Synchrony during Mental Practice’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101, 16369–16373 (2004).

[30] John C. Maraldo, ‘Nishida Kitar¯ o’, in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2024).

[31] George A. Mashour, Pieter Roelfsema, Jean-Pierre Changeux and Stanislas Dehaene, ‘Conscious Processing and the Global Neuronal Workspace Hypothesis’, Neuron 105, 776–798 (2020).

[32] George Herbert Mead, Mind, Self, and Society, The definitive edition (University of Chicago press, Chicago, IL, 2015).

[33] Sylvia Lima de Souza Medeiros, Mizziara Marlen Matias de Paiva, Paulo Henrique Lopes,Wilfredo Blanco, Françoise Dantas de Lima, Jaime Bruno Cirne de Oliveira, Inácio Gomes Medeiros, Eduardo Bouth Sequerra, Sandro de Souza, Tatiana Silva Leite et al., ‘Cyclic Alternation of Quiet and Active Sleep States in the Octopus’, iScience 24, 102223 (2021).

[34] Ifeanyi Menkiti, ‘Person and Community in African Traditional Thought’, in African Philosophy: An Introduction, edited by Richard A. Wright, 3rd ed (University Press of America, Lanham, 1984), pp. 171–181.

[35] Ralph Metzner, The Toad and the Jaguar: A Field Report of Underground Research on a Visionary Medicine Bufo Alvarius and 5-Methoxy-Dimethyltryptamine (Four Trees Press, 2022).

[36] Andreas Nieder, Lysann Wagener and Paul Rinnert, ‘A Neural Correlate of Sensory Consciousness in a Corvid Bird’, Science 369, 1626–1629 (2020).

[37] Abby O’Neill, Abdul Rehman, Abhinav Gupta, Abhiram Maddukuri, Abhishek Gupta, Abhishek Padalkar, Abraham Lee, Acorn Pooley, Agrim Gupta, Ajay Mandlekar et al., Open XEmbodiment: Robotic Learning Datasets and RT-X Models, (2025) pre-published.

[38] Jordan O’Byrne and Karim Jerbi, ‘How Critical Is Brain Criticality?’, Trends in Neurosciences 45, 820–837 (2022).

[39] Lisa Poncet, Pauline Billard, Nicola S. Clayton, Cécile Bellanger and Christelle Jozet-Alves, ‘False Memories in Cuttlefish’, iScience 27, 110322 (2024).

[40] Aditi Pophale, Kazumichi Shimizu, Tomoyuki Mano, Teresa L. Iglesias, Kerry Martin, Makoto Hiroi, Keishu Asada, Paulette García Andaluz, Thi Thu Van Dinh, Leenoy Meshulam et al., ‘Wake-like Skin Patterning and Neural Activity during Octopus Sleep’, Nature 619, 129–134 (2023).

[41] Michelle J. Redinbaugh, Jessica M. Phillips, Niranjan A. Kambi, Sounak Mohanta, Samantha Andryk, Gaven L. Dooley, Mohsen Afrasiabi, Aeyal Raz and Yuri B. Saalmann, ‘Thalamus Modulates Consciousness via Layer-Specific Control of Cortex’, Neuron 106, 66–75.e12 (2020).

[42] Jennifer L. Robinson, Madhura Baxi, Jeffrey S. Katz, Paul Waggoner, Ronald Beyers, Edward Morrison, Nouha Salibi, Thomas S. Denney, Vitaly Vodyanoy and Gopikrishna Deshpande, ‘Characterization of Structural Connectivity of the Default Mode Network in Dogs Using Diffusion Tensor Imaging’, Scientific Reports 6, 36851 (2016).

[43] Jonas Rose and Michael Colombo, ‘Neural Correlates of Executive Control in the Avian Brain’, PLoS Biology 3, e190 (2005).

[44] C. Daniel Salzman, Kenneth H. Britten and William T. Newsome, ‘Cortical Microstimulation Influences Perceptual Judgements of Motion Direction’, Nature 346, 174–177 (1990).

[45] Simone Sarasso, Melanie Boly, Martino Napolitani, Olivia Gosseries, Vanessa Charland-Verville, Silvia Casarotto, Mario Rosanova, Adenauer Girardi Casali, Jean-Francois Brichant, Pierre Boveroux et al., ‘Consciousness and Complexity during Unresponsiveness Induced by Propofol, Xenon, and Ketamine’, Current Biology 25, 3099–3105 (2015).

[46] Claire Sergent, Sylvain Baillet and Stanislas Dehaene, ‘Timing of the Brain Events Underlying Access to Consciousness during the Attentional Blink’, Nature Neuroscience 8, 1391–1400 (2005).

[47] Anil K. Seth and Tim Bayne, ‘Theories of Consciousness’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience 23, 439–452 (2022).

[48] S. Murray Sherman, ‘The Thalamus Is More than Just a Relay’, Current Opinion in Neurobiology, Sensory Systems 17, 417–422 (2007).

[49] T. Shomrat, N. Feinstein, M. Klein and B. Hochner, ‘Serotonin Is a Facilitatory Neuromodulator of Synaptic Transmission and “Reinforces” Long-Term Potentiation Induction in the Vertical Lobe of Octopus Vulgaris’, Neuroscience 169, 52–64 (2010).

[50] F. Siclari, B. Baird, L. Perogamvros, G. Bernardi, J. J. LaRocque, B. Riedner, M. Boly, B. R. Postle and G. Tononi, ‘The Neural Correlates of Dreaming’, Nature Neuroscience 20, 872–878 (2017).

[51] Martin Stacho, Christina Herold, Noemi Rook, Hermann Wagner, Markus Axer, Katrin Amunts and Onur Güntürkün, ‘A Cortex-like Canonical Circuit in the Avian Forebrain’, Science 369, eabc5534 (2020).

[52] Dóra Szabó, Kálmán Czeibert, Ádám Kettinger, Márta Gácsi, Attila Andics, Ádám Miklósi and Enik˝o Kubinyi, ‘Resting-State fMRI Data of Awake Dogs (Canis Familiaris) via Group-Level Independent Component Analysis Reveal Multiple, Spatially Distributed Resting-State Networks’, Scientific Reports 9, 15270 (2019).

[53] Daniel Toker, Ioannis Pappas, Janna D. Lendner, Joel Frohlich, Diego M. Mateos, Suresh Muthukumaraswamy, Robin Carhart-Harris, Michelle Paff, Paul M. Vespa, Martin M. Monti et al., ‘Consciousness Is Supported by Near-Critical Slow Cortical Electrodynamics’, Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences 119, e2024455119 (2022).

[54] Ana Luiza Turchetti-Maia, Tal Shomrat, Flavie Bidel, Naama Stern-Mentch, Nir Nesher and Binyamin Hochner, A Novel Nitric Oxide-Dependent ‘Molecular Switch’ Mediates LTP in the Octopus Vulgaris Brain through Persistent Activation of Nitric Oxide Synthase, (2024) pre-published.

[55] William Turner, ‘Perceiving the Probable Present’, Nature Reviews Psychology 2, 5–5 (2023).