Translating Chinese Philosophy

On the evening of November 18, 2025, the Berggruen “Global Thinkers Series” of lectures hosted an event titled “Translating Chinese Philosophy into the Western Academy: Better Late Than Never” at CITIC Bookstore Genesis Beijing. Professor Roger T. Ames drew on his academic journey to review the work of several generations of researchers in Chinese philosophy. He provided an in-depth discussion on translating Chinese classics to promote philosophical exchange between China and the West, as well as the role of zoetological thinking in understanding Chinese metaphysics.

Professor Lesong Cheng and Professor Martin Powers each responded to Professor Ames’s remarks from the perspectives of disciplinary development in philosophy and the history of ideas. Together, the three scholars explored how cross-cultural modes of expression can reflect and enrich philosophical concepts. They also considered the future of Chinese philosophy, how it might grow through innovative transmission and ongoing dialogue across different traditions.

Roger T. Ames:Reflections on Translating Philosophy and the Idea of Zoetological Thinking

At the start of the lecture, Roger T. Ames shared a group photograph from an international symposium on Chinese intellectual history. Taken when he was still a graduate student, the photo captures a remarkable gathering of scholars who would go on to shape the field of Chinese philosophy: Huang Chun-chieh, D. C. Lau, Wing-tsit Chan, Ted de Bary, Liu Shu-hsien, Kanaya Osamu, On-cho Ng, Julia Ching, Don Munro, Tu Wei-ming, a Vietnamese scholar with the surname Tran, A. C. Graham, Edward T. Ch’ien, and many others.

During Roger T. Ames’s doctoral studies, D. C. Lau’s mentorship deeply shaped his research methods. A scholar who placed great emphasis on language learning, Lau mastered numerous languages, including English, Chinese, Greek, Latin, German, Japanese, and Pali. He also guided Ames in studying languages. For Lau, language was not merely a medium of expression but a vessel of culture. Even after completing his PhD, Ames frequently visited Lau in Hong Kong during summer research trips. The two would close-read texts such as the Huainanzi (《淮南子》) and collaborate on translations of works, including The Art of War(《孙子兵法》).

A. C. Graham was another major influence on Roger T. Ames. Trained as a linguist, Graham emphasized that each cultural tradition carries its own conceptual structure, shaped by the linguistic categories through which it understands the world. He often contrasted the Chinese philosophical lineage with the Western tradition rooted in ancient Greek thought. Greek philosophy fostered a mode of thinking centered on “substance,” one that seeks to define, classify, and uncover the fixed reality presumed to lie behind appearances. This orientation shaped the development of many European languages, including English, and left a deep imprint on the cognitive habits encoded within them. In English, for example, knowing is typically framed as making true-or-false judgments, rather than as a process that unfolds continuously across time and within specific contexts.

Graham argued that Chinese cosmology assumes a world constituted through interdependence. There is no single transcendent principle that stands apart from and explains all existence. Transcendence, he noted, carries connotations of independence and naturally leads to a dualistic framework. When concepts such as tian (天) or dao (道) are filtered by a Greek philosophical lens, they are often treated as if external, self-sufficient, and separate from human life. Classical Chinese thought, however, offersa more relational cosmology. Ideas like the unity of tian and humanity (天人合一) or the claim that “human can extend dao” (人能弘道) highlight a relationship of co-becoming and co-existing. To engage Chinese thought on its own terms, one must first recognize this distinctive condition rather than fitting its concepts into inherited Western categories.

On this point, two renowned sinologists, Marcel Granet and Joseph Needham, offered similar insights. They argued that the key to understanding classical Chinese thought lies in attending to the contextual world, placing ideas within their deeper historical traditions, and understanding the questions they were responding to and the conditions that gave rise to them. Needham further noted that Chinese thought possesses a distinctive sense of order and pattern, one that views the world as an organic whole, recognizes the interrelatedness of all elements, and emphasizes harmony, association, and analogy.

Building on these insights, Roger T. Ames proposes a zoetological mode of thinking, in contrast to traditional ontology. While ontology centers on categorizing what exists, zoetology (生生论思维) redirects philosophical inquiry toward the dynamic processes of life itself. This approach addresses a long-standing challenge in Chinese-philosophy scholarship: it enables a return to the distinctive concerns of Chinese thought, while also building on Joseph Needham’s metaphorical understanding of life and organic interconnectedness.

If the Western philosophical framework of transcendence presents a model of “creation out of nothing” (ex nihilo), in which creator and creation are fundamentally separate, then the Chinese zoetological worldview would envision a cosmology in which creation is always unfolding through change and relationality. Western notions of creativity are often rooted in a religious paradigm: God brings the world into existence, and human creativity is understood as a form of imitation of God’s independent act of creation.

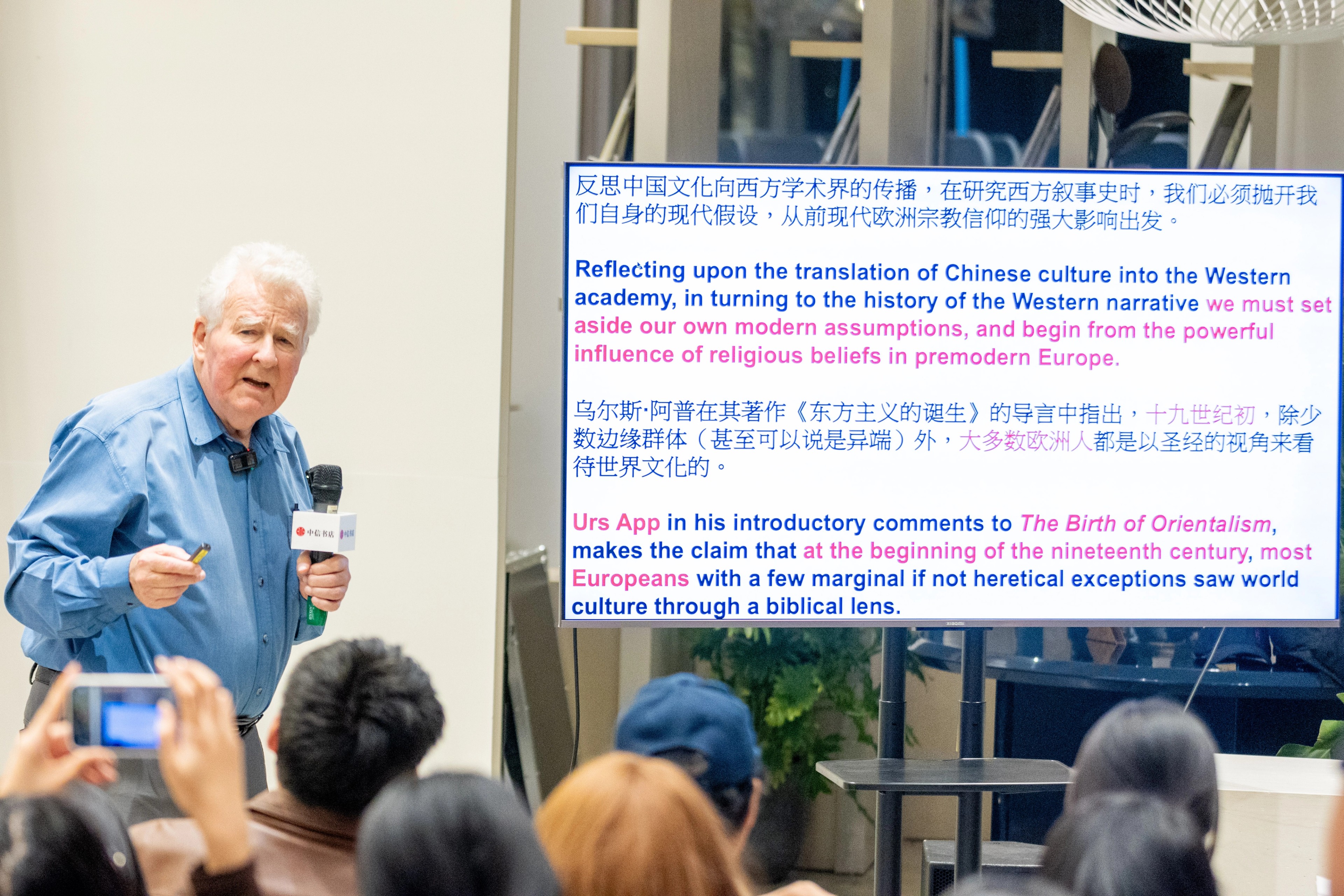

Professor Ames argues that, within the context of Chinese thought, creativity has never been conceived as an individualistic act of sudden breakthrough or innovation. Rather, it emerges from mutually generative relationships within a dynamic and ever-shifting network of connections. In introducing Chinese thought to Western academia, Ames paid particular attention to how Western religious frameworks shaped the vocabulary used to interpret and translate Chinese philosophy, especially in translations by Christian missionaries.

He contends that missionary translations attempted to bridge two entirely different cosmologies by “Christianizing” the Chinese classics, narrowing cultural distance at the cost of distorting meaning. For example, tian was rendered as “Heaven” (as in the Christian heaven), li as “ritual” (religious ceremony), yi as “righteousness” (acting according to God’s will), ren as “benevolence” (modeled on Jesus’s love for humankind), and dao as “the Way” (echoing Jesus’s declaration: “I am the Way, and the Truth, and the Life”).

Ames then turned to a passage from the Daode Jing (《道德经》) to illustrate how Western philosophical assumptions differ from a zoetological understanding of Chinese thought. Considering the line, “道生之,德畜之,物形之,势成之。是以万物莫不尊道而贵德”. James Legge’s translated as follows:

All things are produced by the Dao, and nourished by its outflowing operation. They receive their forms according to the nature of each, and are completed according to the circumstances of their condition. Therefore all things without exception honour the Dao, and exalt its outflowing operation. This honouring of the Dao and exalting of its operation is not the result of any ordination, but always a spontaneous tribute.

Ames pointed out that this translation carries implicit ontological assumptions, reflected in both grammar and vocabulary. It presupposes a separation between the creator and the created. For instance, Legge’s capitalization of Dao signals that the Dao exists independently of the world, much like the Christian God who creates it. It is an intentional cultural reinterpretation that misrepresents the cosmological logic of the text.

From a zoetological perspective, Ames offers the following retranslation:

"The world-growing ecology (dao道) brings all things to life,

And a symbiotic and coalescing virtuosity (de德) nourishes them;

Environing things (wu物) shape them,

And their contextualizing circumstances (shi势) usher them to completion.

It is thus that all things revere the world-growing ecology and venerate their symbiotic virtuosity.

As for such reverence and veneration,

It just arises spontaneously (ziran自然) without anything decreeing it to be so."

This new translation aims to restore dao as an ecological, organic, and natural cosmology within Chinese thought. Dao is neither a transcendent deity nor an object waiting to be defined or judged. It is a continuous, organic, dynamic, and holistic process. Dao cannot be understood apart from the myriad things. It is part of the natural world itself. Moreover, zoetological thinking points to a generative continuity, a lineage of ceaseless relational becoming.

In concluding his talk, Professor Ames returned to the group photograph shown at the beginning of the lecture, reflecting on the spirit of mutual support and intellectual inheritance among earlier generations of scholars. It is through the accumulated efforts of these thinkers that Chinese philosophy has gradually rediscovered and reclaimed its own voice.

Lesong Cheng: Rethinking Translation and the Development of Philosophy as a Discipline

Professor Lesong Cheng expressed his agreement with Professor Ames’s methodology. Translation, he noted, can reveal the internal tensions of philosophical research. The translation of key concepts in Chinese thought not only reflects generational shifts in intellectual interpretation but also shapes the very tradition of scholarship in sinology.

Cheng recalled his experience teaching core concepts of Chinese thought to international students at Yenching Academy of Peking University. He explained that when interpreting classical terms in English, he could feel the differences in cosmology embedded in the languages, as Ames had described. This friction in the process of translation derives not only from linguistic differences but also from differences in lived experience. In the context of an increasingly globalized academic landscape, Cheng argued, scholars of Chinese philosophy must be especially aware of how translation shapes both research and pedagogy. Translation is a dual transformation, “from the dao of tian to the dao of human beings,” and “from lived practice to written text.” It requires continual refinement through concrete and embodied experience rather than merely seeking conceptual equivalence between terms.

He further observed that translating the Chinese classics involves navigating multiple stages of mediation: from classical Chinese to modern Mandarin, and from there into Western languages. In turn, the incorporation of Western knowledge systems is also reshaping the mentality and modes of expression of Chinese scholars.

Martin Powers: Metaphor and Misreading

Professor Martin Powers agreed with Professor Ames’s main argument: language shapes worldview. He further pointed out that the metaphorical systems embedded in language may reveal the fundamental differences between Western and Chinese thought. For example, in the writings of Plato and Aristotle, metaphors of “metallic substances” appear many times. Different social classes are likened to gold, silver, and bronze “substances.” This mode of thinking reinforces and naturalizes hierarchical social structures.

This type of linguistic metaphor also appears in images. There are many examples from art history: God engraving order onto the cosmos, victorious warriors stepping on their defeated enemies, or Hobbes’s Leviathan. All of these images articulate an aristocratic model in which honor is defined by domination over the weak. They reflect and perpetuate a zero-sum group logic and a top-down, substance-based mode of thinking.

In contrast, the Chinese classical tradition features a system of interconnected metaphors. In his Commentary on Zhuangzi (《庄子注》), Guo Xiang discussed the idea of “yunqi gongsheng” (云气共生). Just as clouds change shape under flowing air, all things do not rely on a single authority but coexist through mutual influence. The recurring patterns in landscape painting and lacquer decoration show that the Chinese view of connection is fundamentally different from the Western view. There is no strict separation between subject and object as in transcendent thinking. These textual and visual examples suggest that Chinese philosophy emphasizes “coexistence” rather than “domination.”

In ancient China, this interdependent way of thinking also appeared in institutions. For example, the imperial court and the state kept separate finances, and the emperor was not allowed to divert public taxes. In Han dynasty pictorial stones, the images of Bijianshou (比肩兽) show a relationship of equality and cooperation between the government and the people. They supported each other, creating a framework of renzheng (仁政), which was also a sign of political legitimacy.

Professor Powers also noted that the idea of interdependence in Chinese philosophy influenced the European Enlightenment deeply. Scholars in 17th- and 18th-century Europe admired Confucian formulations of morality, seeing them as a way to challenge theocracy. American Founding Fathers, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, were also influenced by Confucian ideas. Modern Western concepts, including “equality” and “the people,” partly come from translations and interpretations of Chinese thought.

---

Written by: Berggruen Intern Wulan Tuoya

Speaker

Roger T. Ames

Humanities Chair Professor, Peking University

Co-Chair, Academic Advisory Council, Berggruen Research Center, Peking University

Ames is the former editor-in-chief of Philosophy East & West and founding editor of China Review International. He has authored several influential works on Chinese philosophy, including Thinking Through Confucius (1987) and Human Becomings: Theorizing Persons for Confucian Role Ethics (2020). His translations of Chinese classics include The Art of Warfare (1993), The Confucian Analects (1998), and The Daodejing (2003). His work has been widely translated into Chinese, including his recent Sourcebook in Classical Confucian Philosophy (2022).

Commentators

CHENG Lesong

Dean and Professor, Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Peking University

Cheng’s research focuses on early Daoist thought, the history of Daoist ideas, and intellectual history during the Han Dynasty. Adopting a perspective that views religion in terms of faith, he employs methods in textual and intellectual history to analyze Daoist classics within their ancient cultural contexts, thereby contributing to an academic understanding of Daoism in Chinese cultural history. Cheng earned his PhD in Culture and Religion from the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2006.

Martin Powers

Professor, School of Arts, Peking University

Powers has been highly acclaimed as a sinologist and historian of art both in China and abroad. He early on developed a profound interest in Chinese culture and art, publishing four monographs, two of them having won the Levenson Prize for best book in pre-1900 Chinese Studies. He has also edited or co-edited three volumes, and has published more than 50 articles on a wide range of topics. In addition, he designed the educational website chinamirror.net, which provides source materials on Chinese history for advanced high school and college teachers. He has participated in more than 110 scholarly conferences and projects and mentored more than 30 Ph.D. students. He has been instrumental in promoting greater appreciation and understanding of Chinese culture in the West and has contributed to the international standing of the field of Chinese Art History.