III. Machines, Dreams, and Journeying Through Time

- Date: May 18, 2025

- Location: UCCA Auditorium, Beijing

At this event, science fiction writer Bao Shu and artist CAO Shu explore how AI influences human experiences of time, and challenges traditional perceptions of reality—through the lenses of science fiction literature and digital media art.

Bao Shu’s science fiction work has long focused on artificial intelligence, quantum concepts of time, and the construction of memory. Drawing from his daily creative practices, he discusses how machines impact human temporal experiences, emulate the nonlinear narratives of dreams, and use text and image generation to shape psychedelic and absurd imagery.

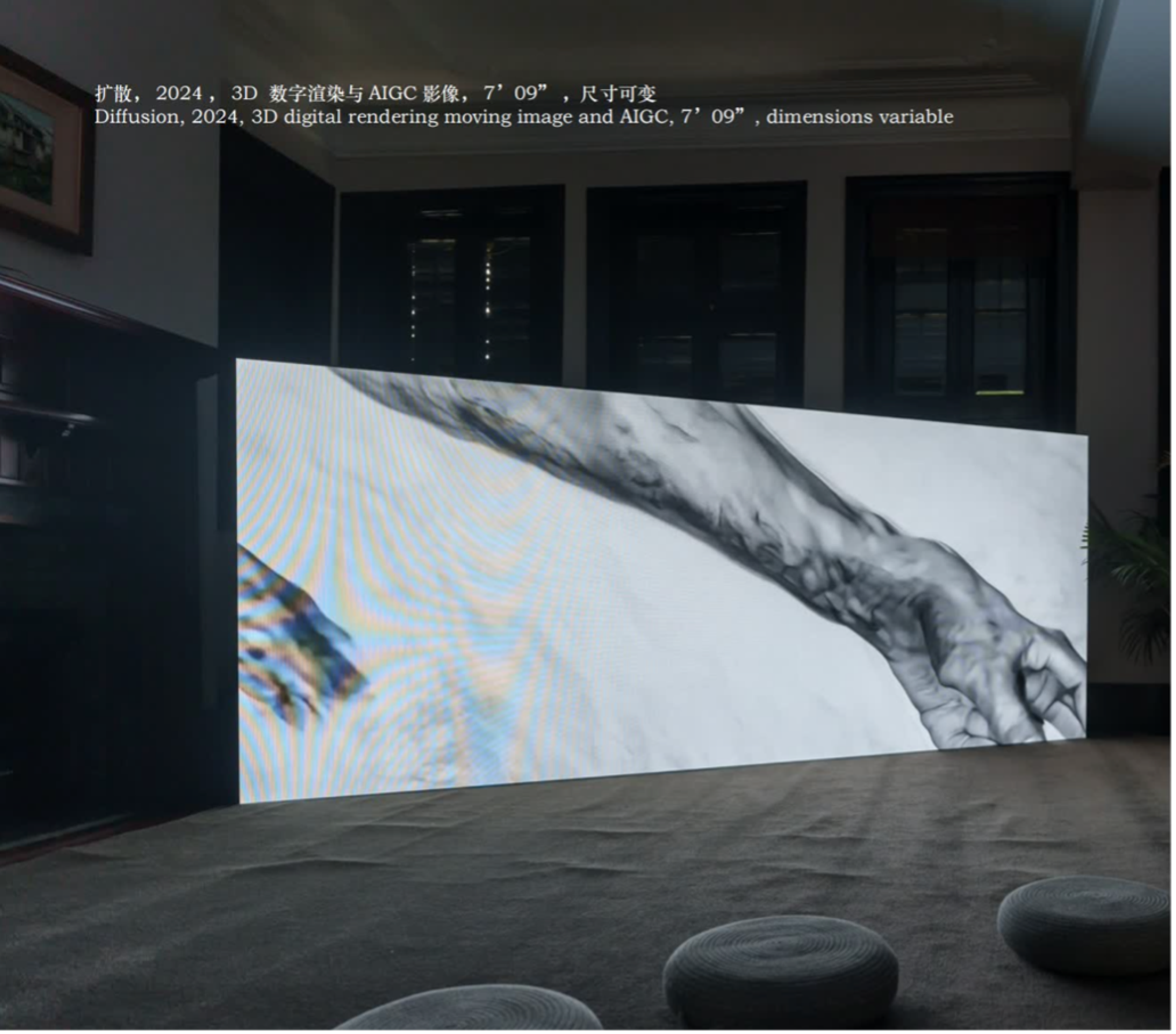

Cao Shu examines its role in image production, the construction of collective memory, and historical representation, while also reflecting on the logic of time travel as expressed in digital media. His recent work Diffusion explores the metaphorical relationship between AI-generated fragmented human forms and historical photographs of nuclear radiation, as well as the connection between photographic technology and the deceased.

Their dialogue centers on the concept of time in philosophy of technology, science fiction literature, and contemporary art. They explore how technology shapes perceptions of reality and narratives of the future, touching on topics such as future intimate relationships, the impact of digital technology on the sense of "reality," and how science fiction thinking can offer new perspectives on history and the future.

This session is moderated by Wu Yiyao, Curator of Public Practice at UCCA.

Event Summary

On May 18, 2025, the third dialogue of the “Symbiosis and Temporal Flow” lecture series was held in a hybrid format at UCCA. The speakers were Baoshu, a science fiction writer, and CAO Shu, a cross-media artist, with WU Yiyao, a UCCA Public Program curator, moderating the event.

In the keynote talks, Bao Shu traced the evolution of time as a concept from the perspectives of both philosophy and science fiction. Drawing from his own work, he examined narrative structures involving time loops, parallel universes, and immortality as diverse “temporary” experiences. Meanwhile, Cao Shu introduced his video installation through the concept of the “replica,” investigating the intersections of cybernetic legacies, AI image generation, and bodily memory. He reflected on how digital media can reconfigure history and reality and explored the interplay between control and chance.

During the roundtable discussion, the two speakers exchanged views on topics such as dreams and sci-fi imagination, family histories and future familial structures, virtual and real experience, and historical sci-fi and time travel. Their dialogue offered a rich convergence of literature and visual art, memory and algorithm, digging deep into the nature of time while envisioning the emotional and structural possibilities of future life.

Baoshu on Writing:

Time Travel and Possible Worlds

As a science fiction writer with a background in philosophy, Bao Shu outlined the conceptual evolution of the idea of time traval from classical to modern thought, and how these shifts have influenced science fiction literature. The inspiration for his science fiction stories stem from the ideas and concepts of phenomenologists such as Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, who emphasize time as an internal structure of the human experience. This philosophical foundation shapes his literary approach: using fictional narratives to disrupt everyday perception and reconstruct the interplay between memory, sensation, and social rhythm.

Time travel, a central motif in modern literature, is rooted in the paradigm shifts brought about by the Scientific Revolution. In the Newtonian era, time was abstracted into measurable linear dimensions. This notion of linear time marked a rupture from premodern cyclical understandings of time based on natural rhythms. With the rise of technologies like clocks and railway timetables, society transitioned from daily routines based on sunrise and sunset to industrial routines governed by standardized time. This transformation profoundly altered human lifestyles and cognitive modes, and sparked a longing for “other kinds of time.”

In this context, time travel is not merely a narrative device but a psychological compensation for the dislocation felt in modern life. As individuals find themselves embedded in fast-paced, fragmented temporal structures, the traditional sense of continuity dissolves, leading to a desire to return to the past or imagine the future. This psychological response is reflected not only in literature but also in daily emotional and social practices. Using his novel The King of Time as an example, Bao illustrates how time travel narratives express modern anxieties and offer frameworks for self-understanding.

From the perspective of literary history, early time travel stories often depended on miraculous or supernatural mechanisms—such as lightning strikes, magic, or divine intervention—as the means of traversal. This was common in 19th-century works, such as Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, but attained modern theoretical and narrative legitimacy with H.G. Wells’ 1895 novel The Time Machine, which proposed a mechanical device as the means of temporal travel. Wells’ scientific framing shifted the genre from magical to plausible, expanding the scope of science fiction.

Beyond linear time travel, Bao also emphasized narrative structures involving parallel universes and multiple timelines. These literary constructs reflect the anxiety of choice in contemporary society, serving as a spiritual outlet for resisting determinism. In the many critical junctures in life—such as college entrance exams, marriage, career decisions—we can only choose one path. This predicament has inspired many works that explore fate and possibility through branching timelines, such as Paul Auster’s 4 3 2 1, the film The Butterfly Effect, and the Japanese drama Restart Life (Re:Life).

This idea of “branching time” also extends beyond the individual to collective history. From the alternative history drama The Man in the High Castle, which envisions a Nazi victory, to the steampunk fantasies of The Difference Engine, such works reimagine historical turning points to expose the contingency of modern reality. Bao also referenced his novel Our Martians, in which he imagined an alternate history where China successfully launched the manned spacecraft “Dawn” in the 20th century, discovered evidence of civilization on Mars, and triggered a space race that led to a radically different global order. This act of rewriting not only revisits technological history but also reactivates suppressed or forgotten possibilities. In Bao’s view, time is not merely a collection of past events but a narrative landscape full of latent potential, with science fiction serving as the art form that explores these “folds in time.”

Time loops have also emerged as a popular narrative model in recent years, offering concrete metaphors for the deadlocks of contemporary life. Films such as Groundhog Day, Source Code, and the Chinese animated series Link Click exemplify this trend. Increasingly, modern individuals find themselves caught in closed circuits of routine: daily work, clocking in and out, content consumption, and social media doom-scrolling. These repetitive cycles, precisely segmented yet inescapable, mirror the time loops in fiction. Here, video game mechanics, especially the “save/load” system, provide an imaginative outlet. In virtual spaces, players experience a kind of temporal sovereignty rarely found in real life: the power to redo, to choose again, to reconstruct the self in the face of failure, death, or loss of control.

Various nonlinear temporal constructs in science fiction, such as frozen time, dislocation, and immortality, highlight the paradox of human longing in the technological age. We desire mastery over time, yet are deeply alienated by our experiences of it. Bao thus concluded by reaffirming that time is the fundamental framework of human experience. While modern society’s regulation of time has yielded efficiency and order, it has also engendered alienation and fragmentation. At the same time, it has opened up rich imaginative possibilities. It is precisely the tension within modern temporality that gives rise to our many fantasies of time, and the future will continue to disrupt and reshape our experiences of time, providing new terrain for speculative storytelling.

Cao Shu’s Video Installations:

Replica Realities and Perceptual Games

Cao Shu’s artistic practice revolves around the concept of the “replica,” a term he expands from its original use in video game terminology into both a creative methodology and a way of understanding the world. Unlike linear, closed, level-based gameplay, the “replica” emphasizes side quests, nonlinear exploration, and free choice. The term also evokes the idea of copies of manuscripts, alternate possibilities, hand-copied texts, or unofficial histories. As a method of creation, it encourages the traversal of multiple paths, moving toward a freer and more authentic state of engagement.

Cao’s work Demon Sugar, a title drawn from futures market terminology referring to high volatility, merges historical research, technological metaphors, and speculative imagination. It is centered around an abandoned sugar factory in Shunde, Guangdong. This site symbolizes both China’s 20th-century industrial legacy and the conceptual stage for the “replica.” The factory calls upon globalized sugar futures trading while also carrying the residue of an unrealized vision, China’s brief 1960s-era exploration of a cybernetics-inspired path to electronic industrialization.

Using the imagery of ant colony algorithms, vertical farming systems, and feedback control loops, Demon Sugar presents a “replica of history” not as a direct reenactment, but as a construction of an imagined trajectory. The drone, serving as a narrative point-of-view, represents a technologically mediated form of memory. In this metaphor, childhood is likened to a rejected ant colony; an external anomaly; a “bug” in the system. To maintain the logic of data control, one must “kill the childhood self,” eliminating chaos and error.

Cao’s Diffusion continues his exploration of technology and the politics of death. Through 3D-rendered imagery and the visual language of AI diffusion models, the work traces the history of image-making from the introduction of photography in 19th-century China to today’s AI-generated imagery. It probes the entangled relationships between images, death, spirits, and hallucination across different historical periods.

Referencing Records from the Brahma Pavilion, a historical text documenting ghost photography, Cao reconstructs how early Chinese society perceived the camera’s soul-stealing power. Creating visualizations through AI diffusion models, he equates today’s image generation to a dreamlike hallucinatory process. The generated images often display grotesque distortions: mutated cats, seven fingers, and even misaligned heads. He also references the “phantom images” left by nuclear tests in Bikini Atoll, radioactive pufferfish that “burned” their shadows onto photo paper, and the lingering imprint of a ladder on a wall after the Nagasaki bombing. For Cao, new technologies not only produce images but also fabricate illusions that are themselves replicas of reality.

Created as a solo video game project, Hidden Like Palm Lines uses a 3D game engine to build a symbolic map located inside an elderly person’s body. The concept emerged from casual conversations with Cao’s mother, which triggered memories related to his grandmother, childhood experiences, and the Cold War-era “dig deep” civil defense campaigns. The game reconstructs these tactile memories, such as intestinal care or matchbox-making, into a sensory memory labyrinth through bodily details.

By intertwining familial bodies, geographical space, and historical memory, the work presents both a fleshy cartography and a tactile history. Tunnels become metaphorically linked to organs. The landscape of mountains and rivers mirrors the “cosmos of the body.” The player becomes a traveler, navigating this terrain to revisit memory, sensation, and history. The game becomes a mnemonic mechanism rich in replica potential, transforming personal experience into a performative space that can be re-entered continuously.

This work offers an interactive interpretation of the replica concept. The installation tracks visitors’ physical movement within the exhibition space and maps it onto the journey of Jesuit missionary Michał Boym, who walked from Kunming to the Vatican in the 17th century. Each step taken by an audience member is logged as a “virtual footstep” pushing Boym forward on a digital map. The 19,000-kilometer journey thus becomes a collective accomplishment, rather than a solitary heroic tale.

The title Remote Dungeon Lock is a mistranslation of “ideology” from the late Qing dynasty, used here to metaphorically evoke the inner mental prisons that people construct for themselves. Boym’s journey—crossing cultures, religions, and languages—is imagined as an ideological jailbreak. This premise is tightly aligned with the work’s interactive logic: every participant contributes to a “collaborative replica” experience, where movement across temporal or ontological boundariesbecomes a shared act.

Through video installations, game mechanics, and cross-media historical archives, Cao Shu activates latent time-branches at the edges of history. The “replica” is no longer a dystopian lament, but a means of intervention. These alternative paths, simulated worlds, and fissured maps become both formal experiments in freedom and protests against the singular narratives and determinism of modernity.

Roundtable Discussion Highlights

(1) Illusions, Dreams, and Sci-Fi Imagination

Bao Shu emphasized the central role of dreams in science fiction. He described dreams as portals to other worlds and thresholds where consciousness and the unconscious meet. Their ambiguity parallels quantum entanglement and the concept of parallel universes in sci-fi. In his novel The King of Time, the protagonist journeys through time and recurring loops via a lucid dream state, turning the dream into a narrative mechanism for time travel.

Cao Shu approached dreams from the vantage point of visual media and art-making, noting their deep influence on his image-based creations. Since 2011, he has kept a dream journal, drawing on Carl Jung and alchemical theory to treat dreams as triggers for visual projects, including works such as Melancholy in the North Temperate Zone and A Corner of the Park. He sees dreams as entrances into deep memory and temporal perception, highlighting the importance of “non-central perspectives” in visual media. Cao referenced Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up as a metaphor. The film critiques photography’s inability to retain detail under magnification, where the blurry pixelation provokes infinite associative possibilities. In contrast, 3D modeling and digital rendering technologies allow every detail to be infinitely enlarged as traceable “vector data,” prompting reflection on the nature of replicas and simulated realities.

In contrast, Bao Shu initially dismissed imagery, believing that creation should be grounded in rational deduction. It wasn’t until a trip to the Louvre in Paris that he felt the abstract but profound “isomorphism” between painting and novel writing, an experience that revealed how visual art can evoke inspiration beyond the limits of reason.

(2) The History and Future of Families

Cao Shu’s work has long centered on individual family history, emphasizing the emotional dimensions of “home” and the importance of oral memory. He noted that the most intimate yet easily overlooked stories often come from family members. While researching topics like nuclear radiation and canal-building, he unexpectedly discovered that relatives had participated directly in these historical events, deepening his awareness of personal history as a blind spot in historical memory. Memories such as his grandfather’s involvement in canal surveying or his mother and uncle’s secret military experiences were not just narrative material, but gateways connecting history and embodied sensation. He further suggested that in the future, families may no longer be organized around blood ties, but formed through shared interests, algorithms, and virtual identities, becoming imagined communities untethered from biological essence.

Bao Shu examines family structures through a future-facing lens. Tracing family-related themes in science fiction from Frankenstein to Brave New World, he noted that the absence or distortion of family relations is often a driving force behind the genre of tragedy. In a technologically advanced future, he speculated that families could evolve into “configurable systems” composed of clones, algorithm-matched members, or virtual beings, replacing the biological family unit. In his anthology, Future Kinship Files, he explores themes that include AI companions, non-human children, and intimacy generated through technology. One example includes parents monitoring children via machines or reconstructing deceased relatives as data-based “immortal surrogates,” acts that may appear loving but risk severing the formation of individual autonomy. Bao acknowledges that biological kinship is ancient but not immutable, and thus warns that technological disruptions to the deep structures of human nature, if implemented through radical social reform, could lead to disastrous consequences, as history has shown.

Though coming from different perspectives, both speakers agreed that the family of the future might not be blood-based. Instead, algorithmic, artificial intelligence, or cloned relational systems could fundamentally reshape how we imagine community and kinship. Cao views this transformation as a challenge to the essence of familial institutions and a potential framework for empathy and reconstitution in post-human societies. However, Bao takes a more conservative stance, emphasizing the evolutionary grounding of family in human nature and cautioning against radical overhauls that ignore its foundational role in social cohesion.

(3) Saving, Loading, and Real Experience: Games and Reality

Cao Shu stressed that games and virtual reality do more than formally replicate reality, they penetrate the very structure of social control and sensory perception. Referencing Slavoj Žižek’s notion that “a father’s glance can be more powerful than violence,” Cao described “virtual deterrence” as a symbol of power. He argued that virtual systems operate effectively precisely because they maintain symbolic meaning rather than physical coercion. Different media forms—painting, photography, 3D modeling—shift how we perceive and feel, enabling the construction of new “structures of sensibility” that break the dominance of existing textual or visual languages.

From the standpoint of science fiction writing, Bao Shu explored how games serve as “second spaces” that offer embodied realism. The save/load mechanic turns games into containers of time, allowing users to revisit past experiences. In games, death is desacralized, becoming just another resettable moment. Bao pointed out that games today are evolving into massive immersive systems with expanding spatial and social dimensions. In the future, they could become parallel “metaverse societies,” potentially replacing real-world relationship networks. He even imagined a unified “super narrative platform” that merges games, novels, and film.

Cao expanded on this by suggesting that in games, death is not an end but a node that can be endlessly restarted. Whereas death in philosophy represents a fundamental endpoint, in games, it becomes devalued, a phenomenon he calls the “hyperinflation of death.” This reflects the modern anxiety of escaping final disappearance. Using the Souls game series as an example, he noted how players endure painful and repeated deaths, only to find that “clearing the game is death” in a new paradox. Bao responded by asserting that it is precisely this “overcoming” of death in games that makes them metaphors for immortality. He cited Arthur C. Clarke’s The City and the Stars, where characters live eternally through identity-switching. Bao argued that future life may become highly gamified, with identity and time freely adjustable, turning existence into a series of scriptable, resettable “save-file narratives.”

(4) Historical Sci-Fi and Time Allegory

Bao Shu highlighted the complexity of historical truth and the need to treat time-travel narratives with seriousness. Citing his novel The Offering of Noodles in the Three Kingdoms, he stressed that time travel should not be trivialized. Entering a different era means confronting unfamiliar languages, systems, and cultures. In the novel, a “six-month training period” is designed to help characters adapt to life in the Three Kingdoms era, reflecting his dedication to historical accuracy and internal consistency. Bao emphasized that genuine historical experience is far harsher and less controllable than its dramatized or symbolic representations, and fiction should reflect this strangeness and risk.

Meanwhile, Cao Shu approached history from the vantage of visual art, arguing that history is not a linear sequence of known facts, but a porous, fluid, and penetrable structure. He emphasized the “mutual flow between historical moments,” a temporal experience akin to the film Cloud Atlas, where the viewer can become a “time traveler,” leaping across temporal fissures. Cao highlighted how sensory experiences—such as smells, textures, and colors—often pierce deeper into historical memory than written text can, evoking otherwise unreachable emotional and mnemonic depths.

Though they work through different mediums, both Bao and Cao underscore the multiplicity and mutability of history. Bao builds tight fictional logics to resist the symbolization of history, while Cao disrupts the linear flow of time through media and embodied sensation.

---

Transcript and editing by Berggruen Intern HE Qirui

Translated by Berggruen Intern Julian Chiao

English edited by Berggruen Intern Nick Corvino

About the Speakers

Baoshu

Science Fiction Writer

2022-2023 Berggruen Fellow

Primarily engaged in the field of science fiction, Baoshu has written nine novels, including The Redemption of Time, The Ruins of Time, and The Seven Kingdoms Galaxy Saga, among others. His short works are available in major literary and science magazines and have been compiled into multiple collections. His works explore themes such as biological evolution and the origins of civilization, near-future private life and ethics, and philosophical investigation on time and space. Many of his works have been translated into English, French, German, Japanese, Spanish etc. He has received Chinese Nebula Award, the Galaxy Award for Chinese Science Fiction, and the Planet Award, among others, and have been shortlisted for the Japanese Seiun Award's international translation category and the Hugo Award for Best Short Story. He is also the chief editor of some science fiction anthologies like Chinese History in Science Fiction and Future Parent-Child Files. His translations include works such as Star Maker and The Cold Equations.

Cao Shu

Artist

Cao Shu engages with a diverse range of media, including writing, photography, 3D digital video, mixed-media sculpture, and video game-based installations. His recent practice investigates themes such as nuclear energy as a ghostly medium, socialist historical science fiction, superorganisms and swarm intelligence, the entanglement of digital technology and memory, encryption systems, the collective unconscious, and speculative inquiries into the Chthulucene, etc. CAO Shu is the recipient of the OCAT x KADIST Emerging Media Artist Award (2022), Exposure Award of PHOTOFAIRS Shanghai (2021), and BISFF Award for Outstanding Artistic Achievement (2017).He was also a finalist for the inaugural E.A.T. PRIZE 2024. He has been residency artist at Atelier Mondial in Basel (2017), Yokohama Koganecho Bazzaar (2019), Muffatwek Munich and Goethe Institute (2023). The Works are collected by KADIST Art Foundation, Australian White Rabbit Art Gallery, Blue Mountain Contemporary Art Foundation, HOW Art Museum, Zhejiang Art Museum. In recent years, the works have been exhibited in art museums around the world, such as Kunsthaus Baselland, Matadero Contemporary Art and Culture Center, M+Museum Hong Kong, Power Station of Art Shanghai (PSA), UCCA Center for Contemporary Art Dune, White Rabbit Gallery Sydney, BY ART MATTERS Hangzhou, Macao Art Museum, OCAT Shanghai, Sleep Center New York, etc. In addition, the works have also been shortlisted for the main competition units of film festivals around the world, including the Leipzig Documentary and Animation Film Festival, DMZ Docs, Message to Man International Film Festival, Annecy International Animation Festival, Milano Film Festival, Ottawa International Animation Festival, Film Festival Hannover, etc.

About the Series

The parallel dialogue series " Symbiosis and Temporal Flow", jointly initiated by UCCA Center for Contemporary Art and the Berggruen Research Center at Peking University, aims to explore the resonance and collaboration between researchers from diverse scientific disciplines, philosophical thinkers, and contemporary artists. The series engages with topics such as "altruistic mechanisms" and "self-awareness", encouraging exchanges from multiple perspectives and examining how diachronic intertextual mechanisms can be formed within authentic and continuous experiences of time.

The three conversations in this series will invite scholars from fields such as biology, medical anthropology, and science fiction writing, to engage in dialogue with artists who have experience in cross-media practices.

The series is initiated and orgnized by Berggruen China’s LI Xiaojiao and LIU Yuanyuan, and UCCA’s WU Yiyao and WANG Youyou.

About the UCCA

The UCCA Center for Contemporary Art is China’s premier museum of modern and contemporary art. Committed to the belief that art can deepen lives and transcend boundaries, UCCA presents a wide range of exhibitions, public programs, and educational initiatives across four architecturally and programmatically distinct locations. Owned by a group of committed patrons, it is funded by donations, sponsorship, ticketing, and proceeds from the commercial activities of UCCA Lab. UCCA has presented more than 200 exhibitions and welcomed more than ten million visitors since its founding in Beijing in 2007 as the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art.

The UCCA is currently presenting “Anicka Yi: There Exists Another Evolution, But In This One” between March 22, 2025, and June 15, 2025, the artist’s first solo exhibition in China and her most extensive presentation to date, featuring nearly 40 works. This exhibition offers a profound entry point into Anicka Yi’s multisensory universe of biology, technology, philosophy, and art, in a bold yet nuanced reflection of the human experience against the background of systems in flux.