II. Natural Code, Body Grammar, and the Allegory of Technology

- Date: May 10, 2025

- Location: UCCA Auditorium, Beijing

Traversing the systematic nature of “natural codes”, the structural logic of “bodily grammar”, and the narrative potential of “technological allegory”, the two speakers transcend disciplinary boundaries to jointly explore key questions:

- Could technology become a new “grammar” for reconfiguring natural order and bodily perception?

- Can the relationship between humans and nonhumans move beyond instrumental logic toward a more open-ended narrative of symbiosis?

LAI Lili, anthropologist and former Berggruen Fellow, examines how the entanglement of technology and the concept of body reshapes and redefines human perception. From the fluidity of the posthuman body to the ethical tensions surrounding material things, she uncovers the intricate interplay between technological practice and lived experience in everyday life.

Artist Guo Cheng, through his sculptural and installation works, dissects the ways infrastructure, digital identity, and algorithmic power co-encode both nature and human society. His practice transforms these abstract entanglements into sensorial and perceptible experiences.

Framed from a decentralized perspective, the dialogue invites the audience into a speculative exploration of technological democracy, ecological perception, and future subjectivities.

The event is moderated by Wang Youyou, Public Practice Curator at UCCA.

Summary

On May 10, 2025, the second dialogue in the Berggruen × UCCA Symbiosis and Temporal Flow series, titled “Natural Code, Bodily Grammar, and Technological Allegory,” was held at the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art. The event showcased LAI Lili, an Associate Professor at the School of Health Humanities at Peking University and a 2023–2024 Berggruen Fellow, alongside artist GUO Cheng. The conversation was moderated by WANG Youyou, a curator of Public Practice at UCCA.

Drawing on materials collected through fieldwork, Professor Lai examined the intricate entanglements among nature, body, and broadly defined technologies within medical practices such as rural hygiene, ethnic minority medicine, and Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART), framing her analysis through an anthropological lens. In parallel, artist Guo Cheng approached these themes through a different perspective. In his exhibition Bug, he explored the dual meanings of "bug" as both a natural creature and a technological glitch. Through the art installation, he responded to the tensions linking the body, infrastructure, and ecological systems.

In the roundtable session, moderator Wang Youyou brought an interdisciplinary perspective to connect the three metaphorical groupings: “natural code,” “bodily grammar,” and “technological allegory.” In dialogue with Professor Lai Lili and artist Guo Cheng, she examined how, through a post-anthropocentric lens and within an expanded temporal framework, we might reimagine the complex entanglements and co-evolution of nature, technology, and the body.

From the lens of Medical Anthropology:

Intersections of Nature, Body, and Technology

The lecture began with Professor Lai introducing her three major research projects that weave togetherthe key concepts of “natural code,” “bodily grammar,” and “technological allegory.” Her three major research projects hope to focus and encompass the tensions and contradictions within and among these three terms through concrete fieldwork and visual documentation.

Her first major research project was eventually compiled into the monograph Hygiene, Sociality, and Culture in Contemporary Rural China: The Uncanny New Village (Amsterdam University Press, 2017). In this monograph, Professor Lai explores everyday lives of villagers in northern rural China, drawing connections between hygiene practices, social interactions, and the intersection of local culture with broadly defined technology.

The lecture primarily focused on the fieldwork presented in her monograph on rural hygiene. Set against the background of China’s “New Socialist Countryside” initiative and the so-called “Toilet Revolution,” Lai observed that although villagers had modernized their homes to better support hygienic practices, the absence of basic sewage infrastructure meant that wastewater and garbage were still diverted into open, man-made ditches and left to be washed away by rain, an arrangement that, even today, remains without adequate resolution.

Drawing on her sustained fieldwork, Lai refrains from claiming that this system directly causes health problems. Rather, she seeks to prompt broader reflections on the relationship between the body, nature, and infrastructure: How do we define nature? Where do we draw the boundary between dirty and clean? And what kinds of complex infrastructural systems are necessary to sustain the forms of “healthy” and “hygienic” living that modern urban life often takes for granted?

Her second major research project, conducted in collaboration with Judith Farquhar and published as Gathering Medicines: Nation and Knowledge in China’s Mountain South (University of Chicago Press, 2021), focused on ethnic minority medicine, particularly examining the traditional practice of medicinal herb gathering. Through field photographs, she showed how each type of medicine—whether dried herbs, simply processed powders and ointments, or deeply refined tinctures—embodies specific environmental conditions, bodily experiences, and technical procedures.

In her view, these medicines are not merely technical products, but are influenced by a combination of factors shaped by soil, weather, sunlight, nutrients, and the local doctors’ skills in gathering and preparing the herbs. All of these factors converge within the human body in a procedure she describes as “gathering.” The juxtaposition of modern microwave and microcurrent therapy devices with traditional medicinal liquors and ointments in local clinics also led her to question the conventional boundaries between “technology” and “tradition,” as well as “modernity” and “tradition.”

In a more contemporary and urban medical context, Lai’s third project addressed Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART). She emphasized the “assistive” nature of such technologies: only when aligned with the natural cycles of human reproduction can these technological interventions achieve success.

In this context, a pun on the Chinese phrase jie haoyun (接好运 / 接好孕, meaning “receiving good fortune” / “receiving good pregnancy”) has gained popularity as a blessing in fertility clinics and online communities. This reflects the broader reality that while ART is perceived as powerful and efficient, its success is never entirely within human control, as “luck” can be just as crucial as the technology itself.

Through vivid and grounded case studies, Lai seeks to guide the audience toward a deeper rethinking of the inseparable, constantly interacting relationships between nature, body, and technology.

The Multiple Metaphors of “Bug”:

Entanglements of Ecology, Everyday Technology, and Infrastructure

Guo Cheng first introduced his solo exhibition Bug, currently on display at Magician Space in Beijing’s 798 Art District. He elaborated on how both fieldwork and conceptual research have influenced his understanding of the interrelations among technology, the body, and nature.

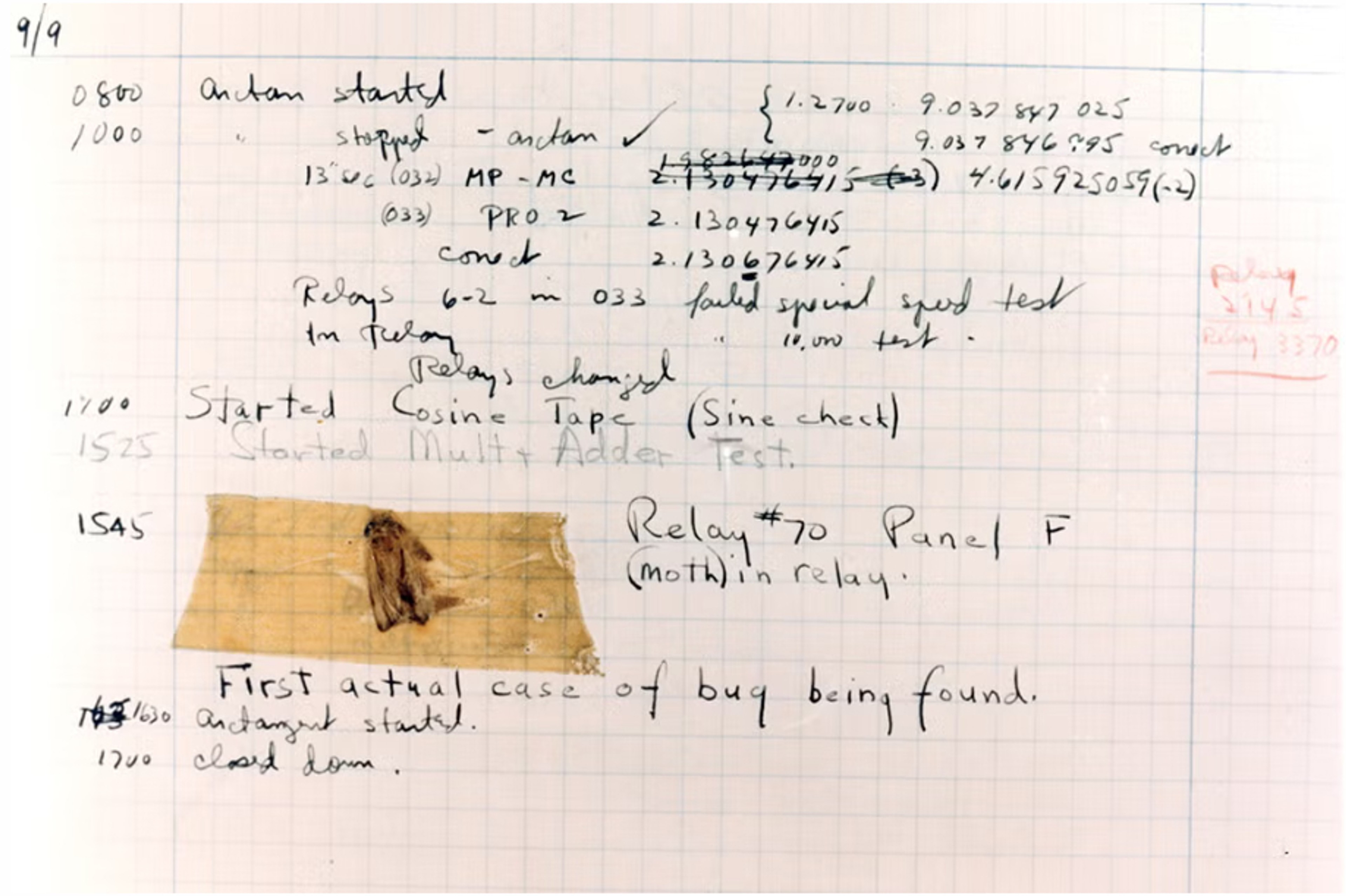

The exhibition’s title draws on the term’s layered meaning in both natural and technological contexts. In nature, a “bug” refers to an insect, while in technology, it signifies a system error or malfunction. Guo cited the well-known 1947 incident in which a moth caused a relay failure in Harvard’s Mark II computer, an event that not only gave rise to the term “bug” in computer science, but also brought lasting attention to insect and dust control in data centers and other technical environments.

For Guo, this historical anecdote inspired a broader reflection on the architecture of data centers, especially those now tucked away in remote mountain regions or submerged underwater. These sites attempt to create a “vacuum within nature,” hermetically sealed from the surrounding environment except for the controlled flow of energy, heat, and data. Yet, the immense cost of maintaining such sterility ironically underscores the deep entanglement between ecological systems and technological infrastructure.

Building on this idea, the exhibition space itself is split into two interconnected rooms. The outer room is brightly lit and sterile, evoking the sensory environment of a data center, while the inner chamber is darker and enclosed by a small window that connects the two rooms. At the heart of the outer space stands Pupa Stone No.2 (2025), an installation featuring two slowly rotating cylindrical “cores” surrounded by hanging network cables and set atop an anti-static floor, evocative of geological core samples extracted from deep within the earth.

A thin green film moves vertically over the sculpture’s surface, revealing textures that resemble cellular structures, insect wings, or the developing patterns found inside a chrysalis. This piece not only evokes the imagined “vacuum” of the data center but also serves as a reminder of life’s common evolutionary origins. It points to the fact that the materials used today, such as minerals and synthetic compounds, are the outcome of geological processes that have unfolded over billions of years, and are ultimately part of the natural world.

Located in the corner of the exhibition, Y29B Bug explores a different scale of time and technology.The title alludes to the Y2K bug, a flaw in early computer systems caused by the widespread use of two-digit year formats. This practice was initially adopted to save memory and reduce costs, as storage space was limited in early computing. However, as the year 2000 approached, concerns grew that these systems would misinterpret the year "00" as 1900 instead of 2000, potentially leading to widespread errors in date calculations, financial transactions, and critical infrastructure operations. While this issue was resolved with the adoption of 32-bit and 64-bit systems, these advancements paradoxically extended computers’ timekeeping capabilities to over 29.2 billion years, far beyond the Earth’s age of 4.6 billion years, and even the 13.8 billion years since the Big Bang.

In this context, Guo assembled an installation composed of a server chassis, a doll representing the anthropomorphized Earth, a customized calendar app, and a mechanical screen flipper that scrolls continuously backward through time. The piece stages a nearly infinite rewind of history, suggesting the absurdity and scale of human temporal imagination.

With this work, Guo challenges anthropocentric views of nature and time. The Earth doll serves as a critique of humanity’s extractive relationship with the environment and our unconscious commodification of natural resources. By referencing Zhuangzi’s Free and Easy Wandering—the opening chapter of one of the most influential texts in Chinese philosophy—he emphasizes the limitations of human concepts of time and the arbitrariness of calendars with the lines, “The morning mushroom knows nothing of dusk and dawn; the summer cicada knows nothing of spring and autumn.”

Crossing through the window into the adjacent gallery, visitors encounter a second set of works commissioned by the Berggruen Institute’s Larva of Time project. Curated by Berggruen Fellow Long Xingru as part of Peking University’s “Creative Futures” program, this interdisciplinary initiative, launched in late 2022, brought together scientists Bai Shunong and Zhang Wei alongside artists Guo Cheng and Zhang Wenxin. After a field expedition to Medog in 2023, the artists developed new works exhibited at NYU Shanghai’s Center for Contemporary Art in 2024.

Centrally displayed is The Moon (2024), a sculpture inspired by the field method of light-trapping insects. The work simulates a chrysalis shape, with a luminous core resembling the moon. For Guo, this glowing object not only draws in flying insects and scientists observing them in the wild, but also symbolically attracts gallery visitors, destabilizing the boundaries between humans and insects, and prompting reflection on the porousness of subjectivity.

Next to The Moon are works from Guo’s Niche Squatter series. The term originates from the ecological concept of the “niche,” an organism’s role and interaction within an ecosystem. During a residency in Netherlands, Guo observed how wind turbines, though seen as clean energy sources, can disrupt airflow, alter temperatures, produce noise, and increase bird collisions. In this sense, the turbines begin to “occupy” a niche of their own, becoming agents that interact with and transform ecosystems.

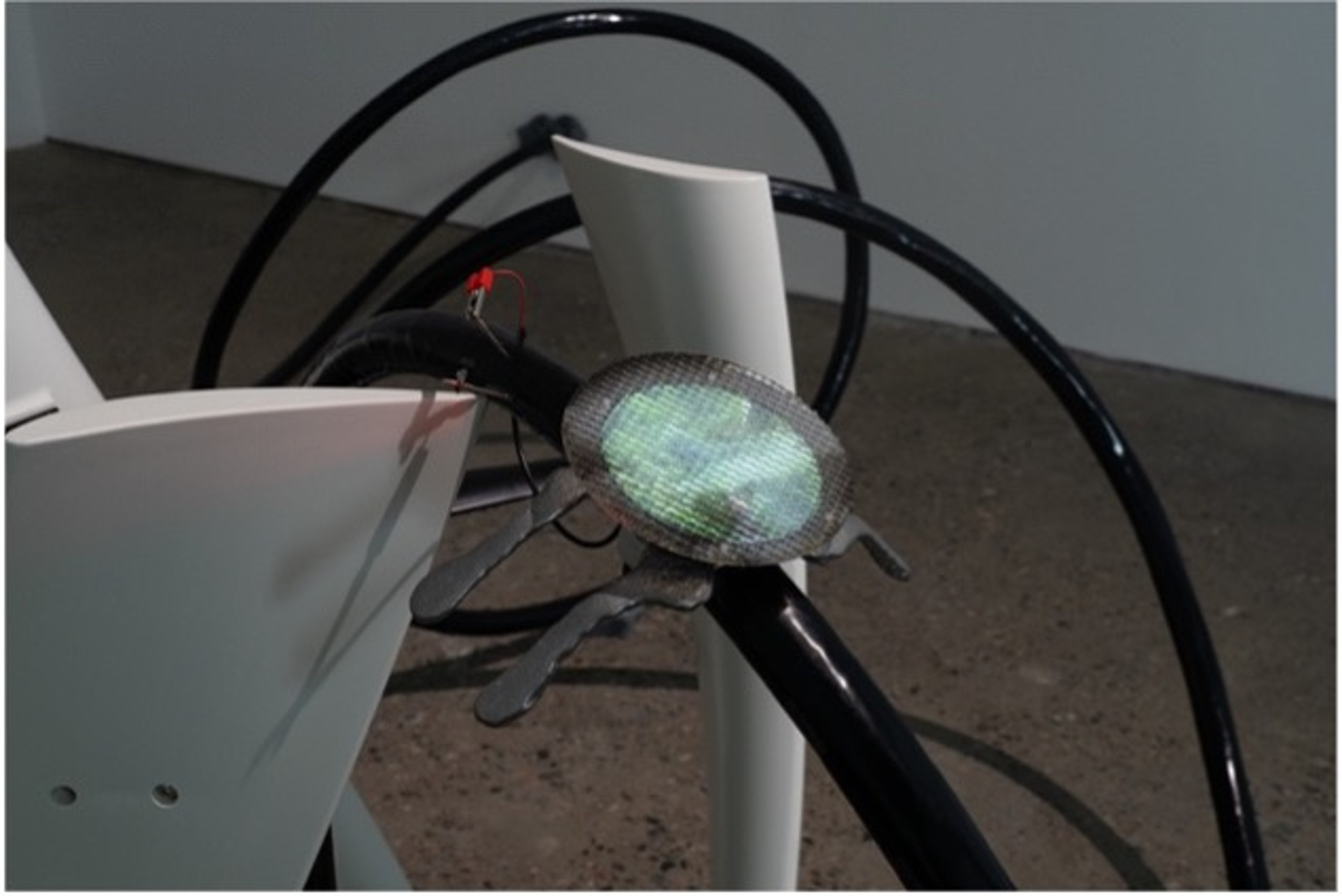

In Niche Squatter No.2 (2024), Guo incorporates vertical-axis wind turbine blades, high-voltage cables, and a small monitor powered by twin micro-probes, which plays aerial footage of Medog. The installation reflects how infrastructure may be partially replacing the ecological functions of other species.

Similarly, Niche Squatter No.1 (2024), made from a leather manual gear shifter, addresses the ecological impact of road construction into Medog; how such roads fragment once-continuous ecological zones, hinder material and biological flows, as well as introduce changes in temperature, noise, and biodiversity.

Mounted on the gallery walls is Guo’s Fog Basker series, sculptures designed to condense atmospheric moisture. These works question what happens when man-made objects are abandoned and begin to interact with their environments? Guo imagines a device left in nature that continuously generates water, attracting animals. Over time, the repeated contact with its metallic surface smooths it down, leaving tactile evidence of multispecies cohabitation.

Nearing the end of the exhibition, visitors must pass once more through the small window into the bright outer room. This return echoes the 1947 moth fatally drawn to light, a metaphor for the instability of human-insect positionality. Guo deepens this reflection by referencing the Da Dai Li Ji—a fascinating but often overlooked text in the Confucian canonin which all living things are categorized as “insects”—and by drawing on biologist Lynn Margulis’s theories of symbiotic assemblages and co-evolution. He ultimately calls for abandoning anthropocentric perspectives in favor of broader ecological consciousness that reorganizes the human-nature relationship and reconsiders what it means to be human.

Discussion and Audience Interaction

In the discussion session, moderator Wang Youyou sought to deepen the exploration of the relationship between nature, body, and technology by drawing from both anthropological and artistic perspectives. She began by posing a question through the lens of infrastructure: Has the meaning of “nature” shifted in our contemporary moment? Are we now encountering a form of “new nature”?

In response, Professor Lai suggested that both “nature” and man-made infrastructure are constantly in flux. She emphasized that “nature” need not be equated strictly with its ecological definition. Instead, it can be understood through more philosophical terms such as ziran (自然) and benlai ruci (本来如此), both of which suggest a more active, inherent quality of nature that resists being passively shaped by human design.

Guo Cheng expanded on this, noting that nature is by definition a fluid and evolving concept, which makes rigid distinctions between old and new problematic. He argued that humans, precisely because we are embedded within nature, often struggle to perceive it in its totality. Just as a fish becomes aware of water only upon leaping out of it, so too did the moment humanity first saw Earth from space reveal the planet’s smallness and our own partial perspective within it.

Wang then shifted the conversation to the body. Beyond nature, might body also exist in a state of flow? As a testing ground for technology, has the body gained new freedoms, or has it become more tightly disciplined?

In response, Guo noted that body does not appear in a fixed or concrete form in his exhibition, Bug. Instead, it is implied to be manifesting through the viewer’s movement, through the installation, and through the narrative logic underlaying it. Lai added that this treatment of body resists rendering it as a clearly bounded or localized form. Rather, it becomes a more diffuse, time-saturated body, one that emphasizes mobility and temporality rather than spatial fixity.

As the discussion progressed to the growing integration of technology into everyday life, Wang posed another question: Is it possible to imagine a post-instrumental relationship with technology, one in which humans and technology coexist symbiotically, rather than hierarchically?

To answer this, Professor Lai cited French anthropologist Marcel Mauss’s concept of “techniques of the body,” arguing that technology does not necessarily require tools. The body itself, and the culturally shaped ways we use it, can be considered forms of technology. To understand the relationship between body and technology, she suggested that we must first redefine both concepts. Once we broaden our understanding of technology, it becomes clear that it has always coexisted with the human condition.

Building on this, Guo noted that from a longer historical perspective, humanity’s development has always been entwined with tools. Even the most ordinary objects in our daily lives embody layers of technical innovation and accumulation. In this sense, technology cannot be regarded as “other” to the human body. Whether in the past or present, it is integral to lived reality.

Given that both speakers’ work draws heavily on fieldwork, Wang posed a final question about method: How do anthropologists and artists observe the field differently?

Lai emphasized that fieldwork is no longer confined to the discipline of anthropology. Methodologically, anthropology calls for openness and attentiveness, but also direction. Without a clear focus, one risks getting lost in the complexities of local life. She also noted that artists may hold unique advantages in the field, such as heightened sensory awareness, aesthetic sensitivity, and a positionality that sometimes grants easier access to certain communities or spaces.

Guo agreed, adding that dual identity of the artist has both strengths and risks. While interdisciplinary borrowing can open new ways of seeing, it can also lead to misreadings or a sense of detachment when unfamiliar methods are applied too freely.

During the Q&A session, one participant posed a question based on personal experience: Is technology internal to the extended body, or does it exist in an intermediate “in-between” zone?

Lai responded by critiquing the mainstream view that treats technology as external, or even oppositional, to the body. She instead emphasized the porousness of bodily boundaries. Guo added that to think productively about the body-technology relationship, we need to distinguish between layers of technology: long-term technological environments, medium-term tools or interventions, and short-term techniques. From a broader temporal perspective, both our living spaces and our bodies bear traces of technological influence. However, not all technical interventions leave lasting effects; some are fleeting. Therefore, instead of seeking a unified theoretical model, we might consider holding multiple coexisting “techno-body” perspectives in tension.

Another audience member observed that Guo’s exhibition appeared to often reflect on temporality, asking whether technology is accelerating the transformation of nature, the body, and the boundaries between them?

Guo affirmed that time is indeed a core element of his work. He pointed to Niche Squatter, in which the contrast between high-voltage cables and microelectrodes reveals the tension between geological time and the fleeting moments of daily life, inviting viewers to experience time as it flows through both technology and nature.

Lai, in turn, argued that if we situate these short-term changes within longer timescales, we begin to see how so-called “technological allegories” and “future narratives” often carry an anthropocentric bias. Thus, rather than simply projecting future outcomes, we must return to a more fundamental question: What does it mean to be human? Only by rethinking this foundation can we begin to truly reimagine the relationship between nature and technology.

---

Transcript edited by Berggruen Intern Ma Lin.

Translated by Berggruen Intern Julian Chiao.

About the Series

The parallel dialogue series " Symbiosis and Temporal Flow", jointly initiated by UCCA Center for Contemporary Art and the Berggruen Research Center at Peking University, aims to explore the resonance and collaboration between researchers from diverse scientific disciplines, philosophical thinkers, and contemporary artists. The series engages with topics such as "altruistic mechanisms" and "self-awareness", encouraging exchanges from multiple perspectives and examining how diachronic intertextual mechanisms can be formed within authentic and continuous experiences of time.

The three conversations in this series will invite scholars from fields such as biology, medical anthropology, and science fiction writing, to engage in dialogue with artists who have experience in cross-media practices.

The series is initiated and orgnized by Berggruen China’s LI Xiaojiao and LIU Yuanyuan, and UCCA’s WU Yiyao and WANG Youyou.

About the Speakers

Lai Lili

Associate Professor of Anthropology at the School of Health Humanities, Peking University, 2023–2024 Berggruen Fellow.

Her research centers on the body, everyday life, and medical practices, with a focus on the transformation of traditional medical knowledges, science and technology studies (STS), and medical pluralism. Lai's major publications include Hygiene, Sociality, and Culture in Contemporary Rural China (Amsterdam University Press, 2016) and Gathering Medicines: Nation and Knowledge in China’s Mountain South (The University of Chicago Press, 2021). She has also published extensively in both international and domestic academic journals.

Guo Cheng

Artist

Guo Cheng is an artist currently living and working in Shanghai. His practice mainly focuses on exploring the mutual impact and influence between established and emerging technologies and individuals in the context of culture and social life. In recent years, his work has centered on ubiquitous artificial objects and infrastructure from a planetary perspective.

His recent solo exhibitions include: “The Park”, Sifang Art Museum (2022), “Almost Unmeant”, Magician Space (2020), “Down to Earth", Canton Gallery (2019). Group exhibitions include: Shanshui: Echoes and Signals, M+ Museum (2024), The Larva of Time,ICA at NYU Shanghai (2024), Elemental Constellations, Macalline Center of Art (2023), Macao International Art Biennale: The Statistics of Fortune, Macao Museum of Art (2023), Chengdu Biennale:Time Gravity, Chengdu Art Museum (2023)

About the UCCA

The UCCA Center for Contemporary Art is China’s premier museum of modern and contemporary art. Committed to the belief that art can deepen lives and transcend boundaries, UCCA presents a wide range of exhibitions, public programs, and educational initiatives across four architecturally and programmatically distinct locations. Owned by a group of committed patrons, it is funded by donations, sponsorship, ticketing, and proceeds from the commercial activities of UCCA Lab. UCCA has presented more than 200 exhibitions and welcomed more than ten million visitors since its founding in Beijing in 2007 as the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art.

The UCCA is currently presenting “Anicka Yi: There Exists Another Evolution, But In This One” between March 22, 2025, and June 15, 2025, the artist’s first solo exhibition in China and her most extensive presentation to date, featuring nearly 40 works. This exhibition offers a profound entry point into Anicka Yi’s multisensory universe of biology, technology, philosophy, and art, in a bold yet nuanced reflection of the human experience against the background of systems in flux.